MAY 27: Today is Farm Day at the Manda Wilderness Agricultural Project (MWAP), also known simply at Nkwichi as “The Farm.” I have been invited to attend part of the day because song and dance are involved. As a gardener at home, I am also interested in seeing the farm itself, and I know I will get a tour.

Although it is still all a little difficult for me to tease out, it is clear to me that there are many strands to what is going on here in the Manda Wilderness. Nkwichi Lodge is the resort side of things. It is a business and employs around one hundred people, making it the largest single private-sector employer in the entire province. Working in the same office as the Lodge staff are Lily and Joe, who are full-time employees of the Manda Wilderness Community Trust. This is a separate non-profit organization, a charity whose economic base is in Great Britain. This is the service arm of what is happening, and it assists the villages with technical expertise and sometimes supplies for building schools, clinics, mills for grinding corn flour, digging wells and generally improving infrastructure. The villages themselves have a sort of congress, which has four representatives from each village, both mfumu and elected. This congress, called Umoji (Unity, or “As One”), determines which projects are priorities and how they might be funded. The villages, lodge and trust all are intertwined in many ways, perceptible and imperceptible.

In addition to all this work, the Manda Wilderness Community Trust provides social opportunities for the villages to get together and engage in community-building time. The choral festival I am participating in is one such project. Others are athletic, such as canoe races, soccer tournaments, and netball for women. A villager who trained in Malawi and brought her knowledge back with her to Mozambique began the latter project.

Finally, the Trust provides education. This can be training on specific skills, such as carpentry or nutrition, or it can be demonstration. This is where the Agricultural Project comes in. MWAP is a demonstration farm that is working towards sustainability. Local residents with certificates in sustainable agriculture live and work at the farm, and volunteers come to assist with new techniques and with getting more funding. All together, it is amazing what is being accomplished with a budget that could be described as shoestring – if one were inclined to be generous!

From time to time, farm staff invite schoolchildren from one village to come and see the farm and learn about sustainable agriculture and crafts such as papermaking that recycle materials commonly found on farms and in villages. Today it is Cobué’s Primary School that is coming for the first time.

Please understand that this is not the typical “field trip” of a North American school. There are no roads, no school buses to take these children to their appointed destination. These students will be leaving from the school at five in the morning, then walking for four hours over very rocky terrain for six miles to come to the farm. They must carry their lunch and an empty cup, as well as any writing utensils and paper they might have to take notes. At the end of the day, they will reverse this process, arriving back at the school after dark (probably between seven and eight). Of course none of this takes into account their walk to get to and from the school from their homes. Next day is another school day. Despite a general lack of adequate nutritional resources, the physical strength and athletic endurance of people here are truly astounding.

I arrived at the farm just a little before the children, whom I take to be middle-school age – between twelve and fourteen – tending toward the older side. When the children come up the path after their walk, they stop single file before entering the open-air classroom / papermaking station / office. From the path, they sing a sort of “we are here and glad to be here” song. Then they are invited to come up and begin the day in the classroom. Their official day then begins with them singing and dancing two more highly energetic songs as the sun begins to warm the farm.

At this point they are allowed to sit, and formal introductions begin. As a guest of the farm, I must once again make a short speech. I choose to do it in ChiNyanja, which as usual elicits a surprised reaction. From then on John, one of the resident staff at the farm, appears to assume I am semi-fluent. That’s okay; I need to push myself a little. All staff, volunteers, teachers, headmaster and students then go around and make introductions and say names. One’s name is extremely important in this culture. The sharing of names is one of the first things that happens in a more extended conversation.

After these introductions, the students are made to sing and dance two or three more songs. June 1 will be “Dia da Crianças” – Children’s Day, so they show us their songs for this upcoming special day. After the songs, we are divided into two groups. The students who are further along in their studies will take the tour in Portuguese, as all advanced instruction in the country is done in this language. The others will get the tour in ChiNyanja. I am put with this group. I work very hard at concentrating to learn as much as possible about the project. I am surprised at how much I get, probably bolstered by my gardening experience at home and how many of the vegetables I recognize. The students are working hard to learn the names of many herbs, vegetables and fruits that are foreign to them: lettuce, arugula, peppers, even passion fruit. All the students and I are fascinated by the papermaking process, and they crowd around and watch with rapt attention as they are shown how an envelope is fashioned from a sheet of paper and a wooden form. One older boy in particular is interested in everything on the farm. He has no paper of his own and is writing everything down with a broken ballpoint pen on his left arm.

After the tour, we return to the classroom. The staff brings out big buckets of very hot and very sweet tea. Two of the older girls from the school are chosen to serve tea and rolls to everyone else for teatime. They dip the students’ cups that they brought with them into the bucket of tea. They also serve all the staff and guests.

After forty-five minutes or so, it is time for two more songs. By this point it is almost noon, and I need to make my way back to the lodge to prepare some more material for my next journey. I take my leave and head back from a most interesting morning.

Three hours later at Nkwichi, we hear the shouts and laughs of the students as they make their way back home. A few of them, tired of the unaccustomed restriction, have removed their shoes. This means they may be making most of the six-mile rocky hike barefoot. One girl appears to have twisted her ankle. She is quite a bit behind the rest of the group, hobbling on her own as best she can. She waves to us as she makes her way up the path, singing to herself. Her friends come back a bit to see how she is doing and tell her to hurry up. They all laugh at the impossibility of this, then her friends run back up to join the rest of the group. She just keeps going.

Everyone just keeps going.

Chicaia's Choir A. Mr. Matifalo is to the far right Chicaia's Choir A. Mr. Matifalo is to the far right Happy news: I do indeed have internet here on Likoma via wireless connection. It is quite slow, however. Once again, thank you for your patience

MAY 21: I spent the day at the lodge at Nkwichi. I used the day to transfer the video I had taken from my phone and iPad onto the laptop in order to make future DVDs for the choirs to have. Volunteers spend their days at the lodge (i.e., when they are not out in the villages or farm) from seven until five at the main office. This way, we are matching the shift of the lodge workers during the day. My work at the lodge generally will involve this video transfer, as well as language study, music transcription, writing articles and any other preparation necessary for the festival itself. Though the work is very interesting, it does not make for blogging material, so the days I spend at the lodge will often pass without much to write about here despite the idyllic setting.

MAY 22: Now it is time to board the speedboat in order to get to Cobué just before noon. Coming in on the speedboat, I watch the fishermen for the first time, working in their canoes. These canoes are usually made from mahogany logs. It must take a very long time to hollow them out. Interestingly, the fishermen do not sit IN the canoes when working alone; they straddle them, using the hollowed-out space to store all their gear and the fish that are caught. They cast a net and draw it back slowly, hand over hand. I can see it takes a great deal of skill, and the lake is calm today. I can’t imagine when a dreaded mphepo kumwera (the wind from the south of the lake that makes it very rough) comes along.

We land at the beach at Julius’ backpacker lodge and head up the hill to James Bondo’s restaurant. The restaurant is a nice single room building with a gravel floor and two tables for sitting plus a table with tea, coffee and water on it. Bibles and schoolbooks are set at various places along the tables. Do they belong to people who work there? The boatmen and Joe, who will be accompanying me this time without Lily, tell me to wait here while they get supplies for the journey. I spend the time watching the tailors across the dirt road. Tailors here set up shop on the porches of other stores, and they use treadle sewing machines. This particular store has two tailors and two machines. Finished pieces hang in a colorful array from clotheslines strung near the porch ceiling. A woman comes and picks up her order, then places the clothes in the basin on her head along with the large bags of rice she had picked up elsewhere. She takes the stairs down from the porch and chats with someone she knows, even as she picks up her child who is tired from walking. The basin never changes position on her head the entire time.

Once all the gear is ready, Joe and I take the short path to Chicaia. This time we actually set up our camp in the yard of the mfumu’s house. On this journey we have the foam pads to put under our sleeping bags. This should make things much easier on our hips and knees. We have a quick lunch of egg sandwiches on bread rolls and make our way to the church for a 1:30 rehearsal.

Mr. Matifalo, the choirmaster, is already there. The choir of course will not arrive for another hour, so we have plenty of time to talk. It turns out that the young Mr. Matifalo has such good English because he grew up in Malawi from a young age and got a degree in Business Administration from a Malawian university. The first week he returned to Mozambique to live with his extended family, he joined the choir at Chicaia; by the end of the rehearsal, they asked him to be their choirmaster! He writes his own compositions, something that is quite rare in this region, where most songs are passed down orally from unknown sources. All the pieces the choir would perform for me today were his originals. He did not know anything about the choir festival, being new to the region, so I caught him up on the details he would need to know.

When the choir comes, it is clear that this chorus has done some work with dynamics. In addition to breathing and posture, we do some work on consistent breath support for softer singing. We have time to learn and run “Chauta” easily, but it is getting dark. There will not be time for “Mtima wanu.”

Chicaia's Choir C [Khango's choir] Chicaia's Choir C [Khango's choir] Interestingly, another choir sets up in another part of the churchyard and begins rehearsing even as we are singing. A member of the choir I am working with goes over and asks them not to do so. They soon leave. This all mystifies me until I learn that there are three choirs in this small church: Choirs A and B each cover half the village of Chicaia (north and south), but Choir C is Khango’s [Cobué’s] choir. The two congregations share the church, which is literally on the border between the two villages. I was working with choir A, but it was Choir C’s normal rehearsal time. The long and the short of it: this means that we will not have to move over to Cobué after all to work with the Khango choir.

This comes as an immense relief to me. Cobué reminds me of a Wild West village, with its saloons and many shops and people on the make. This village of about 3,000 has a bit of a drinking problem, with a good half to three quarters of its inhabitants over the age of about fifteen - shall we say, tipsy - on any given night. It is also true, though, that Cobué is more economically developed than its neighboring villages. It has a health clinic, a maternity clinic, primary and secondary schools, and the large Catholic Church complex as well as corn mills. Cobué is also home to the only immigration office on the lake. There is a cell-phone tower as well as a lighted beacon for boats. Portuguese is more frequently spoken here than in any other village I have been to thus far, mainly because the road to Metangula and then on to Lichinga originates here. Also unlike anywhere else so far, there are people who own motorcycles. Interestingly enough, as with many more cosmopolitan centers (here of course I am speaking very relatively), manners are very different from elsewhere in the region, simply because there are more people with more business and things to do. Strangers do not always greet you on paths, and a greeting may not be responded to if you offer it – unheard of anywhere else! Wild West towns have their charms, to be sure, but not as places to stay in a tent overnight. I am happy we are staying in Chicaia. Am I becoming a country boy at heart?

MAY 23

The choir from Khango will not be coming in until the afternoon, due to school. They are scheduled to begin at 1:30, but it will more likely be 3. Mr. Matifalo however is hoping to stop by the mfumu’s compound at some point to talk to me and ask more questions, so that will give me something to do! Otherwise, I will be sitting in a chair at the compound until 1. Sitting gets very old when one has nothing in particular to do. I spend the morning writing down random memories and observations from my first two weeks in the villages; perhaps I will include some in a future blog post.

By 11, Mr. Matifalo has not arrived at the compound. Joe comes back from collecting socioeconomic data and asks if I would like to walk into Cobué with him to run some errands. Since Mr. Matifalo and I were supposed to meet at 9, I agree. We walked to the Primary School to make sure that students were planning to come to the Farm Day at the Manda Wilderness Agricultural Project. They are, in fact. On the way to the school, whom should we meet but Mr. Matifalo! He asks us to stop by his house later so that we can speak. Joe and I go the farmers market to buy oranges (which really should be called “greens” here) then we go to Mr. Matifalo’s family’s house.

We have a wide and far-ranging talk. He has a lot of goals that come from his time in Malawi, where he heard many advanced choral ensembles in this tradition. He wants his women to learn to develop their head voice (!); he wants an even wider dynamic range; he wants improved tone from his basses. I give him ideas for each, and I encourage him to think long-term. He is in many senses a pioneer with these ideas here, and such things will not be accomplished overnight by any means. I tell him that if he has any way to bring recordings of the groups he admires to play for his group in demonstration, this will help them understand what it is that he is asking for. I know that people who have cell phones here often do file-sharing of mp3s. Though he does not own a phone, maybe someone in the choir who does can help him with this.

He also wants to learn the keyboard so that the church does not always have to pay someone to come and play each week. There is someone from whom he can take lessons, so I encourage him to learn one song at a time, and to “enlist the choir’s help” as he tries to learn. Perhaps phrasing it “I am trying to learn keyboard so that we can save money and time. I can only learn one piece at a time. Which one do you think I should start with?” This will help the choir to be more patient during the transition and perhaps make them more willing to give up temporarily some of their favorite dances and songs.

Upon our arrival, he had told us “You are guests in my home.” This means that we will be staying for lunch. At 12:15 we enter their front room for the meal. As in other homes, the main room is furnished very simply, which gives a quiet, Shaker-like elegance to the setting. There is an Anglican liturgical calendar on the wall, and a working clock with a loud tick. “5:40,” it says. Here there is no table. We eat in the more traditional manner at a floor mat, with two short stools, one on each long end of the mat, for us to sit. As usual, Mr. Matifalo and his family wait outside. We have a delicious meal of nsima, chambo (a large fish of the lake, served whole), and sauce made from tomato. By now I have learned the technique of picking up some of the loaf of nsima, rolling it into a ball with my fingers and using this to dip into the sauce. I am not hungry enough for an entire chambo, but I know that this meal probably cost the family a great deal, since they are not fishermen. The tomato sauce is delicious and appears to have been made from one tomato. I have a feeling someone ran out to buy this food while we were visiting. When we finish, we come back into the yard. We cut up our two oranges to share with Mr. Matifalo, his wife and their toddler girl. After thanks for their generosity, we take our leave and make our way back to the Chicaia church, this time to work with Khango’s choir.

Khango’s choir arrived around 3. We did not have much time, but we worked on breathing, posture and a bit of movement. One of their young basses appears to be developmentally challenged. It is clear that he enjoys singing, and the choir has worked out a uniquely African way to help him in the choir. Each time he begins to meander off pitch, one of the men next to him hits him in the arm. At that point, he simply stops singing until he finds his way again, then he rejoins the group’s singing until the next time someone hits him. Hitting is not necessarily a disrespectful action here; indeed, it is often simply another means of communication among equals. As far as I could observe, he is treated exactly the same way in the ensemble as is every other singer. My heart aches a bit knowing that his presence will likely affect their standing at the festival even as they have found the true spirit of community music-making at the very core of what they are doing. The choirmaster did not feel a need to meet after rehearsal, so I had no opportunity to speak with him and learn more about this or any other matter. They did seem grateful for what they had learned from our hour together, though.

One of the Manda Wilderness volunteers was returning from a job interview in France, so the speedboat that was bringing him back from Likoma came to pick us up in Chicaia at “Peg’s Beach.” Peg Cumberland is a doctor from England who has lived and worked in this region for a decade, hiking from village to village with a backpack of medical supplies, treating those who need assistance. “Dokotala Peg” is highly respected by all in the region. I wish I could meet her, but she is in Malawi at the moment. The speedboat comes, and we all get in and head to the immigration officer’s home in Cobué since it is too late for him to be in the office. Once he has stamped the passport, we all head back to Nkwichi. The lake is beautiful under all circumstances, but tonight is a full moon and the lake is calm. Taking a boat here always seems to make me happy, no matter the weather; but this ride is particularly nice.

Our volunteer’s homecoming was augmented by the fact that it was his girlfriend’s birthday, and staff had planned a surprise combined birthday/homecoming party for them. They set up an area of the beach with decorations, music, dinner and presents. It was all wonderful, and we had a great time. I have to say, after all I have seen and done in the last twelve days, it felt very strange to be there with all the food and drink available so freely. I found myself sometimes apart, gazing north at the lakeshore and thinking of all I had met and the things we had done. There was chambo for dinner, bigger than those we had had for lunch; but as odd as it sounds, after having it at the Matifalo’s, where lunch had been such a special occasion purchased at great cost and prepared with such care for us, it just didn’t feel right to have it tonight again when it came so easily with so little thought as to what was before us and what it took to get it there. I passed the dish along without taking any. I know I will get over this feeling eventually. I wish I wouldn’t.

The unfinished classroom in Mataka. Notice the patched structural crack on the right. The unfinished classroom in Mataka. Notice the patched structural crack on the right. Ways in Which One Enters a Nineteenth Century Novel and Comes to See that Such Things Did Indeed Come to Pass

NOTE: I am about to enter some new adventures. First, Mozambique does not recognize volunteer work as a reason to be in the country. This means I am traveling on a tourist visa. I must leave the country every 30 days. How fortunate Likoma Island is so close! Likoma has electricity (!), but I am not sure I will have access to internet. I will be there until the 10th. From the 11th until approximately the 16th, I will be back in Mozambique and traveling to two more remote inland villages. I will be taking my first chapa, and I will be traveling with someone who speaks only Nyanja and Portuguese for the first leg of the journey. No internet or phone at all on this trip! Please be patient with the ways of travel here. If I am unable to post further in the next four days, look for another update around the 16th or 17th. Thanks for reading!

MAY 20: After rehearsal in Mataka, we return to the compound, say our thank yous and make our way to Chicaia, where we will spend our last night before being picked up tomorrow in Cobue.

We pass Mataka’s schoolhouse. It has three classrooms, but six grades. This means half the children go to school in the morning, and half go to school in the afternoon. This is not an unusual arrangement in many villages in Mozambique when there is a classroom or teacher shortage, and not only in Niassa province. The floor is finished with cement in two of the classrooms, but the third has only dirt and random bricks left from construction of the school. The children have lined the bricks up in rows, apparently to use as chairs. In Ngofi, we saw 100 seven-year-olds in one classroom. I wonder what class sizes are like in the brick and dirt classroom. We notice a wide double crack that runs from floor to ceiling on the end of the building outside the dirt and brick classroom. Can it be fixed? Lily and Joe check the condition of things and try to account for six bags of cement the Trust sent for the school’s floor. Now the school is empty between sessions, but soon the schoolmaster will go out to the forlorn tree in their hard dirt yard and bang on the rusting car wheel hub that serves as the school bell. How long will the roof hold with such serious structural damage on one end? Is it possible the wall could fall when school is in session? We say our farewells and move on.

Although we waited until two in the afternoon to start our hike, it is still hot this day (it is often cooling off by that time). Much of this hike is again in sand, which I think has to be one of the most difficult surfaces to hike on. Still, we reach the chief’s house in Chicaia by around four. Rather than setting up camp right away, we store our gear in the front room of the mfumu’s house and set off to look for choirmasters or members of the choirs in Chicaia and Cobué [aka Khango]. These two villages are very close to each other – twin villages, in fact – but Cobué is by far the larger of the two.

We meet a choir member from Chicaia on our way, with help from the mfumu, who had an errand to run in Cobué and so is accompanying us. Once again there appears to be some confusion with the letters. It is possible that a letter never even arrived in Chicaia at all! Eventually we get the date and time straight with this chorister who promises to inform the rest of the group, and we continue on our way.

On the outskirts of Cobué we stop at a house where the chief told us the choirmaster lived. He was away, but a woman calls for a girl inside who is a member of the choir to come talk to us. It turned out she didn’t know much, but she thought her neighbor might. He was her age, maybe slightly older, and claimed to have the letter itself. He ran home but returned soon, unable to produce it. We tried to make clear to all present that the rehearsal would be the 23rd and not the 22nd as they all thought it was, letter or no letter. That was really all we could do under the circumstances, so we set out for “downtown” Cobué for provisions for the evening meal.

While we were walking down the main road, Joe and Lily spotted Francis from Nkwichi Lodge, and he told us that he was waiting for a chapa (basically a pickup truck that carries as many passengers as can possibly be crammed in the back) to arrive to bring someone home who had gone to Lichinga (the provincial capital) to get supplies. They would then all be returning to Nkwichi that night on the larger passenger/cargo boat that the lodge owns. This meant that we could come home with them if we wanted that night, no last night of camping!

As we were discussing how this would all come to pass, a man came running up to us who turned out to be Chicaia’s choirmaster. He had heard that we were in the area and ran from the chief’s house in Chicaia to find us. His English was excellent, and he and I talked while Lily, Joe and Francis got caught up on the events of the week. It turned out that Wednesday morning would not be good for the Chicaia choir because so many members are in school, so I will train them from 2 – 5 instead. This means we can leave Nkwichi at 10 that morning instead of the 5 o’clock departure time previously scheduled! Better and better….

On the way back to Chicaia to get our belongings we stopped at the Catholic rectory to speak with the Korean priest, who spoke mainly Portuguese, about using rooms there at the rectory for the choral festival. He was very kind and accommodating, and it appears that Manda Wilderness will get the rooms they need for the festival and the following choirmaster training for no charge at all. Cobué has a very large Catholic church, which was burned during the civil war here and still has bullet holes visible on its facade. Just this past year, the church got a new corrugated roof; it had been meeting in the open air for almost two decades. Now they are working on restoring the former school nearby. The entire complex must have been massive; it looks as if it will take a long time yet to get everything done. Fortunately, patience is a virtue in ample evidence at all times here.

As we kept meeting people and as information changed and plans changed, I somehow felt I had entered a Dickensian novel. In so many nineteenth century stories, the characters meet other characters by chance at a dock or on a path, and suddenly circumstances change as a stranger brings unexpected news. I always thought such events were a little far-fetched, but here a minor version of it was happening to us every ten minutes or so! Life is indeed very different without twenty-first or even twentieth century means of communication.

By now, it was getting dark. We came back to the Chicaia chief’s house and had a visit with the amfumu and amayi that was very brief by Nyanja standards, picked up our tents and supplies, and then we were hurrying on our way to the beach at Cobue to be picked up by the Miss Nkwichi, now waiting for us. She is a slower boat than the speedboat I had taken before; the ride was about an hour-and-a-half. We dropped off our chapa passenger and some of his family at the beach near Mala and then continued under the beautiful night sky, a cool breeze making everyone else don jackets and cover up with blankets. I only found it refreshing after all the week’s heat and stayed just the way I was. I drank all the water in my water bottle now, since I would be able to refill it while at the lodge as I need with no worry.

When we get to Nkwichi, a boat is in the way preventing us from docking, so there is nothing to do but take off our shoes, roll up our pants, jump in the lake and wade ashore. A short walk on the shore and we are at Volunteer Beach, where everyone is finishing up dinner. This means we actually get to eat tonight, too! I had a craving for orange Fanta, and had in fact had that craving for about a week. Sometimes I had imagined a bottle of it hanging somewhere above my head while I was out on the paths, as if it were the water in a mirage, always just beyond reach. I drink two Fantas tonight, one for the road and one for the lodge. A toast: To my first hike, I thought to myself.

After nine days, here is a night in a bed (only my fifth night in a bed since I got to Africa); and with a battery-powered LED light overhead to read and write, I am able to stay up until nine this evening… then, a good night’s sleep after recounting to myself over a week’s worth of adventures. I have already learned a lot, and I know this is just the beginning.

The mfumu's house. Can you see the beautiful pergola behind the flag in the center? My tent is to the far left at the edge of the picture. The mfumu's house. Can you see the beautiful pergola behind the flag in the center? My tent is to the far left at the edge of the picture. MAY 18: Joe certainly knows a lot of people in these villages! As we pass on the footpaths, he greets those he knows. There is no “Hi!” “Hi! Talk to you soon,” here. One must ask how each person in the group has spent the day, inquire as to family, and ask where one has been and where one is going and why. There are cell phones, but not many have them, and there simply is no guarantee people who meet on a pathway will see another any time soon. This fact makes it very important to briefly stop what you are doing and to catch up when the chance comes. It does make voyages longer and backpacks feel heavier, though.

When we get to Mataka it is clear that this will be quite different from Chigoma. The mfumu’s house is not near the center of town, though it is closer to the church than was Chigoma’s chief’s house. The family seems rather shy and tends to keep more or less to itself, though all are friendly. Everyone tends to be friendly here, it seems.

Around 4 we went to the church and found several things going on. First, a fairly rowdy group of adolescent girls was gathered near the front entrance step to the church. One had a very young baby (teenage motherhood is certainly not uncommon here). Another girl’s boyfriend or husband was inside, squatting at the doorway of the church with a little boy of about two. The young man was drunk, but I understand him to ask me if I know Chichewa. I answer that I do, but slowly. Judging from their junior high glances and general demeanor, I think many of them are saying unkind things about me, assuming I won’t know. Of course they are right. Joe is shaking his head. It’s all a little uncomfortable.

At the side entrance to the church, two things are happening: first, there is a hard dirt field that serves as a soccer pitch, where a practice is going on. Right next to the church’s side entrance, a group of about twelve is huddled around a very large amplifier and speaker. They have told Joe that they are having a meeting. We soon find out that this was the choir that has been meeting regularly in preparation for tomorrow’s time. The rowdy girls had been in the choir but quit a while back. Upon learning that there was to be special training, they had returned to re-join the choir to get the special training. The conference was to decide whether to let the girls back in the group or not. This being a very delicate matter in any place, let alone a small village where everyone knows everyone, we leave them to their deliberations. We return to eating our own dinners once again: tonight is potatoes and reconstituted soya (a sort of dried tofu one can buy in markets, packaged in what look like chip bags). I like it very much, but I don’t think Joe is fond of it at all.

Mataka choir. Mrs. Chunga, choirmaster, is at the front right. Mataka choir. Mrs. Chunga, choirmaster, is at the front right. MAY 19: After a breakfast of tea, raw peanuts and biscuits [coconut shortbread cookies], we head to the church for the morning’s service. Actually, the first bell calling everyone to church rang a little after 8. The second bell rang at 8:20. We left the compound at 8:30 and got there ten minutes later. One last bell rang at ten ‘til nine, and the priest began the service promptly at 9. How odd the service was scheduled to begin at 8.

There are probably fourteen of us in the congregation as the service starts, and the choir is there, seated on the front right, again facing the altar. Men sit on the right side of the congregation, women and children on the left. Most children leave after about ten minutes to go to Sunday School, held under a nearby tree.

The mfumu walked to church with us. He has his own special seat, a large high-backed chair such as a priest might have, at the very rear of the church right in the center of the aisle. Before the service began, the choir was practicing along with a young man who had brought a battery-operated keyboard along with the amp and speaker we had seen yesterday. The speaker has flashing lights that alternate red and blue when the keyboard is pressed. The keyboard has a transposition function as well as the usual stock drum licks and midi voices. He is trying out many different rhythms, timbres, keys and volumes. Throughout the service, the choir faces the altar, never the congregation, except for the offertory dance when they are not singing. This dance is done in the aisle facing toward the congregation, then back to their seats.

The priest simply announced that the service would begin, and it did. The opening piece was not really a processional, more an opening hymn. Everyone was already in place, after all. Much of the service was sung or chanted, except for the Old and New Testament readings, including the Gospel; and of course the sermon was spoken. During long periods of singing, the choir or congregation consistently go sharp. At some point, the keyboard player simply flips the switch to modulate up a half step and keeps playing. I am learning that sharping is inherent in the style here.

After the Bible readings, there is a very long announcement period, with three apparent testimonials of blessings bestowed (with frequent pointing to the cross), two announcements regarding a town committee concerned with infant nutrition and care, and then the moment I have dreaded: the request for newcomers to come forward and introduce themselves. I try my Nyanja, and Joe only has to re-translate a little from my Chichewa. I feel a lot better now that that is over! Lily and Joe also have to introduce themselves, and then we sit down. We are the only newcomers.

By the time announcements are over, the church is packed, with people seated on the floor. People had been drifting in in small groups all along, but I hadn’t really noticed how full the place was until I had to get up in front of everyone.

The assistant priest delivers the sermon, with active participation from the congregation, some of the sermon being question and answer. After the sermon, we have the passing of the peace, the prayers of the people (sung), the offering, and all other such items one expects before the communion. But just before the priest would begin the actual communion narration, someone announces how much was in the offering: 2000 Kwacha! The congregation applauds. Lily, Joe and I gave 700 of it. After this announcement, someone in the choir stands up and begins to question Lily and Joe over the fairness of the festival the previous year and the qualifications of the judges! It seems this choir won almost every year but last, and choir members want answers. Lily and Joe stand and calmly answer his and the next person’s questions. Obviously, this festival is a serious matter in these villages. The congregation is beginning to get restless and starts to murmur opinions. Suddenly, the mfumu arises from his chair and tells everyone that just because a choir has won in the past does not guarantee that it will always win, and that the group must practice hard and see what happens!

And with that, the keyboardist starts to play, everyone rises and files out. Church is over. Several of the choir members, including the ones with the questions, greet the three of us warmly. This was probably the strangest conclusion to a church service I have ever seen. The service was just under three hours in total.

I am now wondering what this afternoon’s rehearsal will bring….

…..

The afternoon’s rehearsal begins more or less on time at 1:30 – really! The choirmaster from this morning is not here, but another one is: the first female choirmaster I have met: Mrs. Chunga. We work four songs together, with breathing and posture (in what I can see is going to be a continual topic), some tongue position and mouth shaping, some dance, and some placement of the choir – in staggered rows as opposed to files.

The choir learned the refrain to “Chauta” pretty well, and they requested learning the verses tomorrow. It was a good rehearsal overall, even though the church was once again packed, this time with children who didn’t get to witness the soccer game outside between Mataka and Likoma, which was cancelled at the last minute when nobody came over on the boat. I’m hoping tomorrow morning’s rehearsal will be a little less audience-heavy, so we can hear ourselves think!

MAY 20, a.m.: I am very anxious to get going this morning, but based on our previous experiences the other two are understandably not in a hurry. I am thinking Mataka is different from the other choirs, based on their serious meeting of two days ago and the fact that they were at the church at eight for the service and that we began on time for our rehearsal together yesterday. We arrive at 7:50, and sure enough, the choir is waiting for us. I feel a little embarrassed, but there is nothing to do but move on and start the rehearsal.

This morning we reviewed breathing and tongue position. We also worked on facial expression and consistency of movement. By now I have figured out how to charge my iPad on the solar backpack and can now use it to record and show videos. The larger screen makes it a much better teaching tool than my phone was in Uchesse. It is going to be a common characteristic among choirs here that they look at me puzzled when I mention expressivity and consistency. After all, they are really feeling the music and dance! Then, I show them the evidence. This clears things up, and we begin again, with renewed energy and expression, not just internally but externally.

As I am learning the style of choral leadership here, it is clear that this group respects Mrs. Chunga. She has only to start a dance for a piece, and within one step, the choir has joined. I have seen it take several steps in other villages, sometimes with multiple attempts to begin. She lays out the pitches clearly for all parts and provides a clear beginning (often done here by snapping the fingers a beat or two before all parts enter) and a clear stopping point. Nonetheless, when rehearsal is over, she asks me if she is doing well. It is clear she is something of a pioneer. I doubt she gets much feedback. I tell her she is doing very well and that it is obvious the group holds her in high esteem.

Mataka will provide two more soloists for the verses of “Chauta,” and the choir performs the entire piece on its own at their request before I leave. This is something I had hoped might happen: I really wanted the massed choir piece to be something that might be useful to the individual choirs – within a church service or even for the ensemble’s enjoyment. In Mataka, at least, that appears to be realized.

The impressive, large two-story church in Chigoma The impressive, large two-story church in Chigoma MAY 16: Today was a fairly slow day, since we had nothing on the schedule other than hiking from Uchesse to Chigoma. After one last tea and doughnut breakfast at the chief’s lakeside stand, we take our tents down and hike up the beach to Chigoma. Hiking two hours in sand in the Equatorial sun is challenging, but we get there.

Joe does not want to camp on the beach here because unlike Uchesse, this beach would not be secure while we were gone during the day. So… up we go to the chief’s house.

The mfumu of Chigoma has a very nice house by local standards; in fact, it is a pleasant, cozy home by any standard, I should think. The brick house is plastered with cement inside and out, which moderates the temperature considerably. As in Ngofi, a Mozambican flag flies on a slightly crooked wooden flagpole within the chief’s compound.

In our initial visit on the mfumu’s porch, we learn that one of his twin two-year-old granddaughters came down with malaria that morning. This is the same chief who told us on the way to Ngofi that one of his five sons (who was in his thirties) had died recently in Malawi. Death and illness are certainly not strangers here.

After some time of visiting, the amayi invites us inside the chief’s house. In the front room, a simple wooden dining table with two wooden and two plastic garden chairs is set for us on one side, and their malarial granddaughter is lying on a floor mat cushioned with various fabrics on the other. We are served some delicious boiled peanuts and tea, along with borehole water. The table is covered with a plastic tablecloth, then a lace one, very much as one of my grandmothers used to have in her farm kitchen. The walls are decorated with many family photos taped to wall calendars from 2008 and 2009, as well as with local craftwork of small baskets and wooden spoons. A curtain separates us from the back family room and sleeping quarters – three rooms in all in the main home. As with all homes here, the kitchen is either outdoors or in a separate building, so as not to put the smoke in the main house. We thank the amayi for the truly delicious peanuts and head to our tents for a while.

After about an hour, we are invited back, for nsima and beans! It turns out that the peanuts were not lunch, and our hostess is concerned that we have not eaten yet. This will be important for us to remember as we move forward. Manda Wilderness staff tries very hard either to bring all the food that volunteers will need or to pay for food as we go during the journey. Above all, they work at never causing a family to feed volunteers at the expense of feeding themselves or their children. Although I do not think this mfumu’s family would be in such a position, I understand how important this policy is. I feel honored to have been invited to eat in the mfumu’s home. We eat our lunch while listening to the labored breathing of the little girl on the other side of the room. It all seems so incongruous to me, but nobody else appears to give it a second thought. As lunch finishes, the child awakens and thrashes feverishly. Joe goes over and picks her up gently, taking her to her grandmother. Her sister is running around and playing, oblivious to her twin’s condition.

After lunch, we pass the school and head to the large and extremely impressive church to hear the choir practice a little. They are practicing in the shade of a huge tree outdoors. They are quite good; I think it will be fun to work with them tomorrow. On the way back from hearing four of their songs, we buy onions from one of the market stalls. The onions will improve the taste of our spaghetti since it is quite plain otherwise.

The night is very noisy until about 11 or so, because the mfumu’s nephew has a bar that is part of the compound. I am beginning to understand a bit of the routine of a village at this time of year: first off for my part, around 8 o’clock, I am ready for bed! I think it is because I am so much like a little child here, trying to observe and learn and understand and remember everything. I get a little overwhelmed by the end of the day and tire quickly after the sun sets at 6. Dinner is usually at 6:30 or 7, and the village falls fairly quiet during that time. Villagers, of course, stay up and visit one another when dinner and the day’s chores are over. Bars begin to play loud, repetitive music until about 11 or 11:30. Then, all is quiet until 3 in the morning, when roosters begin to crow. People really start stirring around 5 (earlier if they work in another village), and the children who do go to school – not a given here – go around 7 in most villages if their school meets for a full day or they are in the “first shift” in villages that do not have full-day schools due to space limitations.

MAY 17: Rehearsal, scheduled to begin at 7:30, began between 8:30 and 9. We rehearsed until 11:45. Around three hours is about right for a rehearsal, I am finding, given the physical activity, singing and the heat of the day. Once again we cover breathing and posture, keeping the head up and back straight even when bent over in a dance, how to stop songs together, and keeping the choirmaster in the front and center for the directing at the festival. This choir is more experienced here, so they learn both the refrain and verse for “Chauta.” We do not go over “Mtima Wanu” as a larger group, but I will have a chance to work with the choirmaster and two soloists this afternoon, so I plan to teach it to them to teach the choir after we leave.

I ask the choir if they have any questions. One singer asks a very good question about stagger breathing, and I explain how that can work. The choir is concerned that the judges will penalize or even disqualify them for breathing mid-phrase, or for coughing or stumbling onstage. I work hard to explain that the ensemble’s music making and movement in dance are most important. It is becoming clear that choirs do not know what judges are looking for at the festival. I will try to make that more a part of my presentation without making it a main point. The competition aspect of the festival is very important, and I am learning that villages take these honors very seriously. People know which village “won” the choir festival, the canoe races, the netball games and the soccer games in the Wilderness Area for many years back. I want to try to emphasize the idea of making music together and learning from one another more, but that is not how people think of the event at all here right now; it will probably take much more time than I have here to foster that spirit of togetherness in music.

In the afternoon, I meet with the choirmaster, Mr. Chingomje. He asks me many interesting questions about easing tensions within a chorus, encouraging good attendance and timely attendance (!), and also about touring – his dream is to take his chorus to Malawi to tour. Apparently some church choirs in this region use touring as a fundraiser. I tell him I will do research to see what is available for cultural grants for touring, but of course I can make no guarantees.

Two of the three soloists from the morning return to master the verse of “Chauta.” I estimate them to be fifteen or sixteen years old. We have a wonderful time singing the piece a few times in harmony then Mr. Chingomje leads us in a closing prayer.

The two soloists, Joe and I walk back to the center of the village together. On the way, one of the girls is trying to read aloud Joe’s book in English on sustainable fish farming, as well as his questionnaire for his socioeconomic data. She does quite well, pausing only for the word “bamboo,” which she was pronouncing like bambo – the Nyanja word for “father.” She asked Joe to tell her what it meant, and he told her to ask me. “Nsungwi,” I said. “Ah! Nsungwi,” and she kept reading as we walked through the cassava fields in that hot, hot sun. I wonder where her intellectual curiosity will lead in a village like this. Will she be a leader in the village? the church? or might she move some place else to further her education? Chigoma has a more extensive school than most villages, but it only goes to Level 7. I fear she is past that already.

The chief has one sensitive grandson of about ten who spends much of his time quietly on their porch, daydreaming or carefully organizing an extensive bottle-cap collection. He plays quite happily with the other children, but he seems happiest just to think on his own. He observes us visitors very carefully, though he tries to conceal just how intently he is taking in everything we do. I wonder what place he will find in the village as well.

When we arrive back at the compound, the amayi has already prepared a feast for us: nsima, beans and goat meat. This is indeed a special meal clearly prepared intentionally for us, and there is no way we could have gotten back from the church to cook before she had begun preparing this food for us. There is nothing for it but to accept the honor of this dinner in their home and to enjoy what has been cooked. To do otherwise would be disgraceful. As is customary here, the guests dine alone inside the house while the family eats elsewhere. When we are finished, we go out to find the mfumu and amayi and thank them for their hospitality. Back inside where we have just left, Lily and I see the children of the compound rush into the front room and grab the pots, most especially the meat pot. They dip their fingers in, grabbing at nsima, beans and meat with sauce, and lick the pots clean. Clearly, they were promised our leftovers.

It is very easy to see why Christianity has such a strong place in Nyanja culture. The New Testament speaks directly to daily life here, not some historic past that bears no relation to “modern times.” The villages, the fishermen, the waves that come up unexpectedly, the farmers, the famines that strike without warning, the illness, the death, the children, the aged, the poor, the rich – and make no mistake: we are the very, very rich here, struggling through the eye of the needle…. All the parables are NOT just stories here. They are very real, very close, and they carry great promise to those who hear them and learn them by heart.

Mr. Joe helping set up camp. The fishermen's shelter is just out of range to the right. Mr. Joe helping set up camp. The fishermen's shelter is just out of range to the right. MAY 14: After Lily and Joe meet with the local Manda Wilderness Committee of Ngofi, we leave for Uchesse. I have run out of borehole well water by that point, and there is no chance to go back and fill up again. The hike from Ngofi to Uchesse is long and hot, and once again I feel dehydrated. It is amazing how much the hot sun and my lack of water color my perceptions. Maybe it was just too much adjustment for me to make all at once, and I should go back to give it another chance; but I cannot say that Ngofi was one of my favorite places.

Uchesse, however, I already know immediately upon our return, is. I liked the mfumu here when we first passed through. His is very tall, very funny and very levelheaded. When we returned to his home from Ngofi, the amayi [this word technically means “mothers,” as the plural is used to be polite, but it is used to refer to the female head of the household as well] informed us that he was at the lake, where he usually is during the day, sitting under a fishermen’s shelter selling tea and doughnuts (unsugared doughboys) to the fishermen as they come in or prepare to leave for the day’s catch. Sure enough, after a five-minute walk down to the lake, we find him there at his post. Along the lake in the villages, there are long wooden shelters, between twenty-five to fifty feet long and fifteen feet wide. They are open to the air on all sides, with thatched roofs. These provide a place for the fishermen to hang out in some shade between outings, to chat, to eat, to drink tea or any other beverage they might choose, and even to sleep. They are altogether very pleasant places.

The chief is set up in one corner, with a large plastic tub filled with his doughnuts, a thermos of hot water on a tray with spoons and a few mugs (Minnesota Fair! Happy Mother’s Day! and other such used American mugs that have somehow made their way here), a measuring cup with a sieve bottom, a bag of tea leaves, a bag of sugar, a tin of powdered cream, and a basin for washing cups. The chief tells us that you get two doughnuts free when you buy your tea. He is quite a businessman! Lily purchases tea for all of us. I can only manage one doughnut because I am still so dry, but it is quite tasty. To make tea here, you reach in the bag, take a pinch of leaves, put them in the measuring cup on top of the wet leaves already there, then pour the water from the thermos. It is delicious.

We settle in and start to chat, along with any fishermen who are not asleep. I am getting used to the fact that nobody expects white visitors to speak Nyanja, even at my relatively basic level. The chief asks me if I am from Malawi or Canada. His English is very good. I tell him I am from the United States and he wants to know how I came to speak Chichewa – this is almost everyone’s third question after my name and where I am from. When I tell him by books and by computer, he is as surprised as everyone else here that such resources exist for the local languages.

…..

At this point I should probably clear up the confusion you may be feeling about Chichewa and Nyanja. Locals regard them as two separate languages, but as far as I can tell from my experience until now, they are more like separate dialects, as far apart as English in Southern Texas and in Scotland, say. With effort, I can use my Chichewa learning to get by, and Joe is beginning to teach me some of the differences. Based on what I learned at home, Nyanja as a rural dialect preserves some “old-fashioned” elements, particularly in formality and politeness, which have been lost in the language of the cities of Malawi. I am also beginning to learn the sprinkling of common Swahili words that one encounters being this close to Tanzania: Karibu! Asante!

…..

The conversation turns to my solar backpack. Single solar panels are actually fairly common here; one can buy them in many town markets, and homes frequently power an LED light or two and a radio from the battery attached to them. Young children of about seven or eight are occasionally tasked with climbing onto the family’s roof three times a day: once early in the morning to place the panel, once mid-day to turn it, and once at night to bring it down so it doesn’t fall or get taken overnight. Restaurants usually have enough of a solar array to power loud sound systems (as I discovered in Ngofi). The chief asks me how much my solar backpack costs. Uh-oh. I round the amount down to $350, though it was probably really a little closer to $400. The fishermen want to know how much that would be in Malawian Kwacha, the more common currency here than the Mozambican Metical. The chief immediately whips out a solar calculator and comes up with 1,200,000 MK, which is too high by almost an order of ten; it is more like 140,000 MK. Still, I feel embarrassed, knowing that the average annual family income in this region is 40,000 – 120,000 MK. I will soon learn that this is sort of inquiry is simple curiosity, with no apparent hard feelings at all – but I do not know this yet, and I tell them that I bought the pack with a grant rather than my own money, which is true. I’m not sure if they understand the word “grant,” but I suppose it makes me feel better. The fact is, I would imagine many present were interested in the technology and looking forward to the time it becomes affordable for them. Such a thing would be very practical for the fishermen and for farmers working in a field all day. While we are talking, someone comes to buy some more tea. The mfumu lifts the creamer container, only to find a black scorpion hiding underneath, the most dangerous kind of scorpion that lives here. Calmly, the mfumu slices the scorpion in half with the handle end of a butter knife, so as not to dirty the business end for the customers. He places the knife back in the tray with the mugs.

Uchesse's choir. Mr. Mngulu's hands are clasped in prayer. Uchesse's choir. Mr. Mngulu's hands are clasped in prayer. Joe meets with the women on the beach, who sit under a separate shelter near an open fire doing cooking and washing, to ask if he might use one of their pots and a bit of their fire. He cooks spaghetti and sauce again and brings it over. A toddler who lives with a woman in a separate shelter, a businesswoman from Likoma, wants to try some. She likes it, once she figures out how to use a fork to get it in her mouth.

After our chat, we went back to the chief’s house and picked up the hiking boots Lily had left on our way to Ngofi. They have been beautifully sewn all the way around, and glued in many places for extra security. We also arranged to pay the family for some mustard leaves for our evening meal. We then went to the church to observe some of the group’s rehearsal. I recorded and videoed some of it, they gave us a speech of welcome, and we left to let them finish this preparatory rehearsal in peace.

We pitch our tents on the beach here. We can do this because the chief often returns there at night to sell a little more tea to the shift that comes to shore in the middle of the night, so there are always people around for security. We wash some of our clothes and ourselves in the lake. By this time the inevitable entourage of children has gathered around Lily’s tent, where she and I draw sand pictures with them. I am not a good artist. They get my njobvu (elephant) right away, but one boy thinks my mphaka (cat) is an mbalame (a bird)! After drawing a ng’ona (crocodile) with an open mouth, which they all get, I make an appropriate sound effect they like, and with laughter, we part ways so that we can all have dinner.

For dinner we have rice with mustard green “sauce” – a green vegetable, my first in four days! Needless to say, it tastes phenomenal. I am finally getting re-hydrated, and I try not to dwell on the fact that the chief’s family gets its water from a borehole and that I could have had that water on the way up two days ago if we had known. After making our thanks for the greens and the use of the fire, we hike back to the beach, and I fall asleep to the sounds of the waves and the motors of some big boats leaving for the night, along with the shouts and laughs of all along the shore.

MAY 15: We woke up to a nice, cool morning, although I think it was a little cold for Joe and Lily. One of my tent poles had snapped at the top overnight in the wind, so my tent was a little lopsided. It certainly hadn’t bothered my sleep! The sand felt good after the hard ground at Ngofi, and my hips felt a lot better, since I tend to sleep on my side.

Breakfast here in this part of Africa is always tea and a plain bread roll, but since we are in Uchesse, we do as the Uchessians do and have doughnuts again with the chief.

We meet the choir again at São Barnabe Anglican Church at nine o’clock for a rehearsal scheduled to start at 7:30, with Mr. Mngulu, the choirmaster, and twelve more in the ensemble: three sopranos, five altos, three tenors (including choirmaster), and two basses. One bass and one soprano in particular have very good voices. Nonetheless, this choir has been disbanded for two years and only met again for the first time a week ago. As you can imagine, this creates many issues.

We spend our morning working on breathing, vowel formation and seating formations for practice. They had been sitting on three parallel benches, with the women facing out toward the congregation and the men gathered on the backbench facing in toward each other and away from the women. I suggest they rearrange the benches to a U shape, with the men in the middle and the entire group facing one another. They take this suggestion and change it to reflect cultural norms here, so the basses take one leg of the U, the tenors and male altos (quite common here) take the middle, and all the women take the other leg of the U. At this point they begin to hear their harmony and tuning better, though there is still a long way to go.

They wanted more instruction on vocal technique, so I have the younger girls try to find some head voice to extend their range. The local style for sopranos tends more to a nasal belt, but all get the general idea right away. We sing for a while with a floating descending [hu] in the middle of the treble clef for a while, five notes descending. It seems to help a bit, but of course this will need more than a few hours of instruction to develop. We also worked a little on dance unity (!), which I find a little easier to comment on than I had expected.

I think this group picked up “Mtima wanu” better than “Chauta,” though Joe feels differently. We break for lunch and head back to the chief’s home for a spaghetti and sauce, with borehole water to drink. My favorite word in the English language is becoming “borehole.”

Our afternoon rehearsal was scheduled to start at 1:30, so we began at 2:30 and worked until 5. I am starting to get used to this concept of time. There are few if any clocks in these villages; so all time must be an estimate. Some people at the rehearsal are the same and some are different. We work on the same principles as we did in the morning, as well as ways for the choirmaster to start and stop the group. I think of using my phone to give them immediate audio and video feedback, which is a very successful technique. Most of them have never seen themselves before, so it comes as something of a surprise to them how they actually are moving as opposed to how they thought they were moving. I also show the choirmaster more ways that he might work with the group teaching parts. All in all, it was a productive afternoon. The choirmaster asks if we can come back two or three more times before the festival. We take the group’s picture, and we leave the church to the sounds of adolescent voices – not just the ones in the choir - singing “Chauta” at the top of their lungs.

At night, we eat as guests of the chief’s family in his yard. Cooking is often done in the open this time of year. The amayi cooks dinner for us while the mfumu mixes the dough and cuts his doughnuts. Then when we are served, they put on a pot of oil to fry the doughnuts. Lily and Joe express surprise that the mfumu knows how to cook.

“Ah, I learned to cook in Lichinga [the capital of the province] in the Seventies. I worked in the restaurant. I want a job at the Lodge, Lily.” He is teasing of course; the lodge is a long way from Uchesse. Joe starts to laugh.

“A job?” Lily asks.

“Yes. I know how to cook all kinds of things.”

“Ah, but we have many cooks already at the lodge, I am afraid.”

“Not for the lodge, Lily. For you. I will be your cooker-man.”

Joe finds this absolutely hilarious. I am thinking of the soft spot I am learning that Lily has for fresh doughnuts, and the picture of the mfumu making fresh doughnuts for her every day at Nkwichi is indeed funny. Lily smiles as well as she says, “I will certainly give it some thought, chief.”

Amayi gives us nsima (a sort of firm round loaf made of corn meal or cassava that one dips into sauces) and Joe exchanges a bag of our uncooked rice for it. Nsima with beans is very filling, which is of course the point. They also serve us a smallish, bony fish that I found difficult to eat in the dark, since it was very bony. This is a very filling meal, and we head back to the tents full and tired from a long, productive day.

One more night in Uchesse under the stars at the beach

The altar and choir at São Bartolomeo in Ngofi The altar and choir at São Bartolomeo in Ngofi NOTE: The lodge reached its bandwidth quota for the month last weekend [May 26]. The lodge bought a little more bandwidth to pay bills and make bookings, but obviously my blog is not their priority! This meant I could not post any further updates until the beginning of this month. Again I’ll resume where I left off. I really should be able to catch up soon, since much of my time at the lodge this past week was spent in the office – so this week at Nkwichi was considerably less eventful.

MAY 13: We had a quick breakfast of a roll and some tea (liquid!) before leaving for the church. I was so dry I had to dip my bread in the hot tea just to be able to eat it. We also filled our water bottles with very cloudy water from a well, added our purification tablets, shook the bottles and waited for a half an hour. The water was chalky, but it was safe, and it was water.

We arrived at the church for training at 7:30, as promised in the letter. The choirmaster (that is the title one uses here) of Ngofi’s São Bartolomeo Anglican church, Mr. Chauli, came to meet us at the church at 10. There are conflicting stories as to who did not deliver the letter telling the choir that there would be a rehearsal this day, but the most common story was that the chief had given the letter to an unknown woman who was supposed to deliver the letter to the choirmaster but forgot. Mr. Chauli was very apologetic, but he assured us he could have the choir assembled at the church by one o’clock. I had my doubts. If people were working in the fields or on their boats, how would word even get to them?

We returned to the compound to have lunch and to meet the mfumu, who seemed rather unhappy. The mfumu of a village has multiple roles, functioning as something like the mayor, for which he is compensated (minimally) by the government of Mozambique; but he is also a counselor, representative and host to outside groups and a source of news for the village since he must travel considerably for various meetings. The position is hereditary, but, interestingly, it goes to the eldest nephew, not the eldest son. An aged petitioner came to the mfumu to tell him of his illness, his lack of money to treat it and how minimal assistance had been at the clinic. The chief listened to his story, but it was clear he was not interested. Eventually he simply got up and left, leaving the man to sit there for about five minutes. Then the old man looked at me somewhat sheepishly and said, “So, I am going,” and left as well. The cause of the chief’s unhappiness may have been domestic, but discretion demands that I leave some things I have heard in my travels out of my account.

When we met back with Joe at the end of lunch (he had gone into the village to collect socio-economic data, one of his jobs with Manda Wilderness Community Trust), he told us he had seen Mr. Chauli heading back to his own part of the village at one o’clock! Nonetheless, Lily thought we should go back to the church and wait until five o’clock, since he might have been attempting to gather the group. What else was there to do, after all? There was a decent breeze and it was shady in the church, so it seemed like a good idea.

The church was near a popular bar. In fact, I had passed by the bar earlier in the day; and in the friendly banter in Nyanja that went back and forth, I asked a man who was singing along with the sound system in the bar why he wasn’t joining us to sing in the choir. “Ah, no, my friend. I prefer to drink.” Little did I know early in the morning that I would be hearing that exact same one song blasting from the bar and making its way up the path to the church for the entire day. Repetition is very common and very popular here, and it is not uncommon at all for people to play one song for hours on end, or to sing a song many times over as well, repeating the same verse.

The church is a lovely building of handmade bricks and cement plaster. The banner above the altar announces that it was built in 1936. The priest has a very loud goat tied up right outside the parsonage next door. This goat sounds as if he is saying “NOOOOO” or “NOW!!!!” depending on his mood. Two chickens, one pure black and one pure white, have free reign of the church. I take a moment to ponder the symbolism.

While waiting at the church, we take advantage of a working borehole well right outside, and dump the chalky water in favor of delicious, clear water. I don’t know if I will ever get enough. It’s amazing how much knowing that that source of water was there right outside the doorway affected my outlook and ability to think clearly.

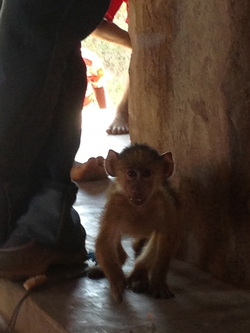

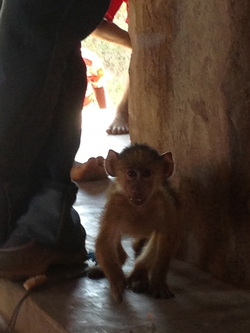

Our new friend. Waiting to be baptized? Our new friend. Waiting to be baptized? At three, the noise of young children screaming and laughing came closer and closer. A young man in his twenties burst in the main entrance of the church, followed by at least twenty children. In this man’s hands was a leash. The leash was attached to a baby baboon, which promptly set up court at the baptismal font, to the delight of the gathered crowd. It was very cute, but Lily was afraid that the baboon would never be able to be released in the wild now that it had imprinted the young man as his parent. The young man claimed to have found him wandering about alone, so who knows whether the baboon would have survived regardless. After fifteen minutes of general merriment and picture taking, the crowd left, and the chickens resumed their rightful place among the pews once they ascertained that the baboon was gone.

The choir then began arriving at around four o’clock. First had come Mr. Chauli at 3:30, who seemed very apologetic but did not think there would be much chance of rehearsal. Lily told him if nobody came in the next half hour we would leave. Soon, people begin drifting in in twos and threes. By four, there are about fourteen choristers. We start with “Mtima wanu,” the round I brought. I started with it because it is a nice, simple melody and seemed like just the right message to start rehearsal. The group picked up the melody and words quickly, but it soon became clear that a round is NOT in the tradition of the area at all. The group does not understand singing a piece without harmonizing, let alone part of the group waiting while another part starts to sing – they begin harmonizing independently almost immediately. After a few unsuccessful attempts at explaining how a round works, I want to start over yet again; but I remind myself that I am not here to force unasked-for musical ideas – and the fact is, the harmony is still tonic and dominant, so the “round” could still work, even if it means various villages come in at various times and sing their harmonies. I set the piece aside and move on.

Next we do “Chauta,” which is much more successful. We don’t have time to learn the verses, but we get the refrain down very well.

After this I learn just how much choirs are the same the world over. Mr. Chauli says that these songs are very nice, but how will they help them in the competition? Lily explains that these are the two pieces that all the choirs will perform together, so it is necessary that all choirs learn them while I am in each village. I point out that we would have had much more time, but the letter confusion meant that we were down from five or six hours to one. I offer to see one of their pieces, which they perform for me. It is difficult to critique because not everyone is there, even of the twenty who will be at the festival (in fact, Ngofi has 82 choristers in two ensembles when they are all there), but I do offer a few constructive criticisms.

Their attention then turns to the Choral Festival itself, and their questions go to Lily and Joe. Why can’t the festival be in Ngofi, like the canoe races, and not so far away? Will the food be good this year? Who will the judges be and are they qualified? Does the choir really have to keep to the required maximum limit of twenty singers at the festival? The two answer the questions calmly and politely.

At this point, we say farewell to one another, and the three of us head back to the compound. The bar has changed songs; apparently there is one song that they play all day, and another they play all night. Thankfully, the sound fades and disappears before we get back to the chief’s.

I cannot tell if our hour together was beneficial to the chorus or not. Lily seems to feel it was successful, especially given the time we had. Joe tells me he likes the second song, “Chauta.” And so my first meeting with a choir in Africa comes to an end.

MAY 12: The day began early, or at least early for what I have been used to: it is quite light out here by five in the morning, and we were trying to get on our way by seven thirty or so. Lily (the manager of community projects here) and Joe (Lily’s assistant for community projects and my guide and translator) were running around the office, packing tents, sleeping bags, and food for our eight to nine day journey. One thing I realized right away was that my solar backpack was NOT going to be adequate for this sort of thing. I had packed in it a few changes of clothes, toiletries and medicines, my passport, and all my recording equipment – audio and video, as well as the sheet music, a pitch pipe, and several wonderful pencils from the URI Department of Music to give out as gifts to members of the choirs (the types of pencils that change color from blue to white when you hold them or apply another heat source). I felt pretty good that I had managed to cram all of this into my backpack and the dry sack I had brought along to protect equipment on boat rides. When I saw Lily and Joe would have to carry my tent and sleeping bag because there was no way I could do it with the backpack I brought, I realized things were going to have to change for the next trip, but it was too late now. They gave me a big water bottle (and each took one for themselves), and we were off.

We set out around eight in the speedboat, bound for Cobue (which is also known as Khango). As you may be able to tell from the previous entry, Cobue is sort of the “big city” of the area; and Lily and Joe had to buy some more provisions for our trip. At a market stall, they bought eight bags of pasta and five or six cans of tomato sauce, which Joe promptly loaded into his provisions bag. His backpack was enormous – his was wide and Lily’s was tall. Both of them were very kind and bore the extra weight without saying anything. “Never again,” I resolved.

Normally, they would have disembarked in Cobue and have continued from there, but since this was my first time hiking in the Equatorial sun, we got back into the boat and traveled another hour or so to the next village north, Mataka. Here we left the boat, put on our packs and got ready for the hiking portion of the day. By now it was around ten o’clock or ten thirty, and the sun certainly was rising high in the sky. The nights can get quite cool here – I estimate between 55 and 60 F, but the days quickly warm up into the upper 80s or 90s.

We had four villages to go through (townships, really): Mataka, Chigoma, Uchesse and finally Ngofi, the northernmost village in the Manda Wilderness. The estimated time of the hike was three to four hours, but I learned quickly that all reckoning by a clock here must be an estimate. At all times, if one meets someone that anyone in the hiking party knows, everyone must stop and have a brief visit before moving on. This happened rather frequently, because both Joe and Lily travel extensively in the villages.

I spent the first part of the hike simply absorbing the fact that I was actually doing this. There are no roads in this area at all, only footpaths. The paths are usually hard-packed dirt, but sometimes are stony. In places, tall grasses close in to the path and hit your face over and over as you walk through them. Streams and rivers often have bridges, but they are made of one or two (three if you are lucky) branches lashed together, and they wobble as you walk on them. I was beginning to understand that I should not bring a dry sack next time, since I needed both hands for balance. Still, I managed. And I was looking around – everything – the plants, the birds, the houses, the smells – everything was new to me, and I was trying to take it all in.

While in Mataka, we passed the church during worship. Joe and Lily asked to call out the chief of the village to remind him of our return in a week to work with their choir. They had sent a letter to each village asking if each would like us to come on such-and-such a date to work with their choir. These letters are not sent by post office, since I haven’t seen one yet; rather, they are delivered by friends or trusted acquaintances. It is very important to follow up on a letter one has sent, since that friend or acquaintance may forget to deliver the letter, and it is entirely possible (indeed, fairly common) that it did not reach its intended destination. While the three of them were conversing, I looked into the church (and felt a lot of stares coming my way, but that was to be expected). The choir was singing and dancing at the time, and I really wanted my first glimpse of an African choir. To my surprise, they were facing the altar, not the congregation. As I thought about it later, it made sense, since this was worship and not a performance. They were quite good, and seemed to be in their late teens or twenties for the most part. I felt much better having an actual reference point as to what sort of choir I might be working with during the week.