My tent outside the mfumu's compound. I love the pattern on the home in back! The building on the left is for temporary grain storage. My tent outside the mfumu's compound. I love the pattern on the home in back! The building on the left is for temporary grain storage. JUNE 13 (continued): Just as the chief of Matepwe had predicted, we arrive at the home of the mfumu of Magachi in almost exactly one hour and a half. The chief here is very kind; his graciousness is all the more impressive due to the fact that neither he nor the choir received any of the letters the Trust had sent. We are essentially walking into his home completely unannounced. Nobody seems particularly disturbed by this, however – least of all the chief. Perhaps this happens on a regular basis due to the remoteness of the village.

Once again, Mr. Joe and Mr. Marcos will stay in the front room of the mfumu’s house, while I will stay in the tent but just outside the compound. This seems to disturb Joe, and in truth it is a little bit of an unusual arrangement here. Though Joe normally stays in this place when he is here, my tent will be near a central path for the village. I really don’t feel any sense of worry myself and assure him I will be fine there. We set up camp. As they go to unload their belongings, the usual crowd of children begins to gather to see my crazy house and funny looking me. I entertain them with some silly dances, which they enjoy immensely. Marcos walks in on my performance. “You are making the children very happy,” he says in Nyanja. The longer we are on the trip and the more comfortable we become with one another overall, the more I have enjoyed Marcos’ company. He actually takes time to teach me the names of things and gently corrects me when I make grammar or usage mistakes, especially in the differences between standard Chichewa and Nyanja. This I really appreciate; how else am I going to learn?

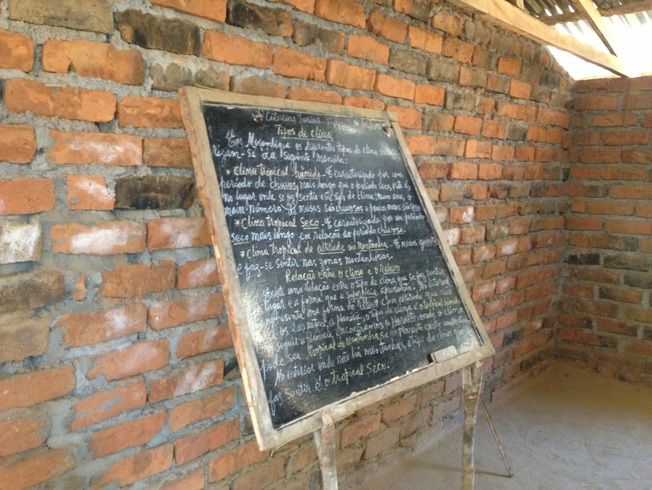

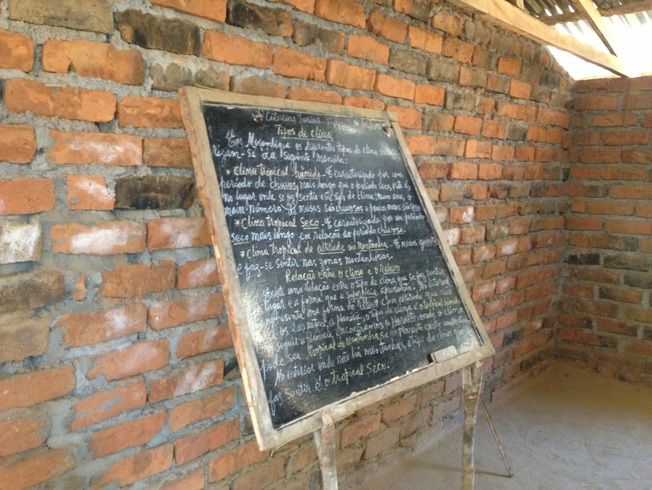

A lesson on Mozambican climatology, neatly written in Portuguese at the Magachi school A lesson on Mozambican climatology, neatly written in Portuguese at the Magachi school Once again a choirmaster has apparently been informed of our presence as if by magic, and soon we hear the metal pipe that serves as the church bell here calling the choir for a meeting and rehearsal. Magachi is quite far from the action (thirteen miles even from Mcondece), and this is the first time in three years that a choir is up and running here in time for the festival. By 4:30 or so, all are assembled who are able to come, and we have speeches followed by the choir singing two songs seated. We all agree that 9 – 11 will be good for the choirmaster and any adults who can come to meet with me, and then the children will join us after school at 2. The choir is very much younger than most choirs I have seen so far, with many fifteen years old or under. I will need to alter my instruction accordingly.

Tonight we had dinner in the chief’s “backyard,” their walled-in family compound. We do separate cooking from the family over an open fire in the corner. A granddaughter named Maria who also sings in the choir and whom I estimate to be about twelve years old has apparently been assigned to assist us in whatever way we need. Fortunately our needs are few. We are having spaghetti, but the family is having nsima, which always takes a long time to cook. As we are eating and they are waiting, the chief tells us the story of the name of Magachi. Apparently the Yao were in the village first, and their name for the place was their name for the local river as well: Chizulu. They grew mostly beans, however, so the first Nyanja settlers heard the Yao name for beans all the time: Magachi. That is the name that finally stuck. I think it is actually a nicer sounding name and say so. This seems to charm the chief, who appears to have taken a real liking to me and makes earnest attempts to talk to me. He tells me the name of their Anglican Church is Igreja Santa Maria. He asks if there are any churches named after Saint Mary in the United States, and I tell him that there certainly are – very many! He likes this response as well.

The only thing I feel bad about is that everyone is so cold. Many people actually are wearing winter coats, though I estimate the temperature to be in the low 50s. Of course they only have open windows and no blankets. Overnight I hear the sounds of coughing coming from many huts. For once, though, my own heritage and upbringing is to my advantage; for me the weather is not only comfortable but a positive delight after all the heat and sweat. I only hope my immune system holds out for the rest of the trip.

JUNE 14: Before beginning our morning with the choir, we once again make a detour to the school to present school supplies. I love the optimism of this village. Though tiny and remote, they have taken the time to construct a sign outside their two-room schoolhouse: “EP1 de Magachi” it proudly proclaims: "Escola Primaria Uma de Magachi.” Public School Number 1? I think it will be a while before number 2 comes along…. As I said, I love the optimism, and the school is very well maintained. I am liking Magachi as a village more and more.

The choir of Igreja Anglicana Santa Maria, Magachi. Mr. Barnabas Santhe, choirmaster is on the far right. The serious expressions so many choirs adopt remind me of Nineteenth Century American rural portraiture. The choir of Igreja Anglicana Santa Maria, Magachi. Mr. Barnabas Santhe, choirmaster is on the far right. The serious expressions so many choirs adopt remind me of Nineteenth Century American rural portraiture. Though scheduled at 9, of course we begin our session at 10. It is indeed mostly adults. They sing two of their songs then want to launch right into learning “Chauta.” I talk them into a breathing and posture lesson first. With the adults separated from the children for the first time in any village, I will be able to give the two different breathing lessons I have always wished I could! I am able to take extra time demonstrating and practicing, then I have the choir try the last song they did using this new posture. The choirmaster, Mr. Barnabas, is astounded at the difference in sound. The second the song is over he jumps over a bench with a huge smile and lunges for my hand for a big handshake and even a high five of sorts – a kind of sideways two person hand clap. Gradually the children were coming in from school. Apparently this school was shorthanded as well, this being salary time, and the teacher felt that sending the children to rehearsal would improve his class size. It made sense to me.

We began to work a bit on dance. They had always been rehearsing in rows, which here invariably means sopranos (almost exclusively children) in the front row, altos (grown women and unchanged boys) in the second, tenors the third and basses in the fourth. One of the problems with this system (among many) is that the children cannot see the adults behind them in order to properly learn the dance. Many choirmasters do not stand in front of their group; rather, they correct them from the side. This is a confusing vantage point for a child, and they frequently do poorly. This choirmaster was so exasperated with one child who was perpetually on the wrong foot that he yelled “Iwe! Ndiwe mzungu?” [“You! What’s the matter with you? Are you white?”] At the first opportunity, I encourage the group to consider rehearsing dance in a circle, so that the less experienced can observe the more experienced and can learn the correct foot to use by observing the two people next to each singer. It takes a few tries, because the children always want to look across and then get confused by the apparent opposite footing, but after a few gentle explanations things get better.

This group, which again is trying to get itself started after years of desultory attempts, has its detractors: a couple of hecklers have come to try to derail the process. One is a young man who apparently has nothing better to do, the other a slightly older woman who was once in the choir and keeps telling them how bad they are and how lazy. Eventually the choir deals with both and tells them they must leave the church. Thankfully, they do.

By the end of the first rehearsal, the choirmaster is beginning to come to the front and center to give crucial directions, the first two rows are together in the dance, and the group has more energy and sound. Unfortunately, the men are not as accurate in their dance as the children are now, but this is a little awkward since the men are the disciplinarians of the group and cannot be directly corrected by a stranger in front of children. I am hoping the circle technique will improve their precision with time.

The afternoon began more or less on time. The group does not have much discipline yet. The ensemble tells the choirmaster when they do not want to sing a song he has suggested and then refuse to sing it. People talk over each other and the choirmaster and sometimes tell him what to do and how to do it. Still, we manage six songs and three videos. We ran “Chauta” with movement, and I manage to hand out the pencils that the University of Rhode Island Music Department has sent as special gifts; they are “magic” pencils that are blue on the outside when cool and white when warm or after being held in the hand. These pencils are a huge hit whenever I can hand them out, but I only have enough if the choirs are under twenty each, and even then I may not have quite enough. This choir passes the test, so they will get their pencils now. Others will just have to wait until the festival, when the twenty singer maximum rule is brought into play. Of course there is no such rule for ensemble size in the villages, thank goodness.

We are not finished until well after five (and don't forget it gets dark here by around six), but it was a very productive day. The choir tells me they will be coming to the festival this year, so that is at least one more choir than before!

Once again on the way back to the compound, I must watch children being cruel to animals. I really do not know how or why dogs and cats stay domesticated here. Most people throw rocks at them and shout “Iwe!” [You!] and “Choka” [the impolite command for “Get out of here!”] frequently accompanied by hitting, though I have not seen any kicking as I have heard happens in nearby cultures. Dogs and cats are never fed anything other than small table scraps if any are left; otherwise they must forage. A cat [mbuyao, I learn from Marcos, not mphaka as in standard Chichewa] came by the compound and gave such a pitiful meow, I wanted to give it something from our dinner, but didn’t dare. I do understand it would be a huge “waste” of food.

At dinner, the chief asks me if I can move to Africa for the rest of my life to teach the villages how to sing songs. I tell him it sounds wonderful, but I don’t know how my wife would feel about it! Joe laughs. The chief asks to see a picture of my family. I have one, but it is on the computer I did not bring on this trip. He tells me to send him one when I get home; he wants to see it.

I look up at the stars, still trying to get used to the changes – the Big Dipper is upside down, spilling its contents towards a North Star that is only imaginary here. The Southern Cross is high in the sky. Orion, who is backwards and always lies down, has already disappeared from view. There is almost always at least one shooting star every night, but tonight all the stars stay in place. As always, some of them seem to change color though: blue to white to red and back. The night is clear and cold, and I am content and getting sleepy. I bid everyone goodnight and go to my tent to settle in.

Tomorrow is a very big hike as we head back home. I feel ready but a little nervous about my first all-day hike. I hope I can do it.

It is true: I have always considered myself to be lucky and a little cursed at the same time to have been born into two such different families. On one side of the family, there are generations of teachers and preachers. My Grandpa was a preacher, and Grandma was a first grade teacher. I grew up admiring this side of the family, wanting to emulate their mannerisms, their interests, and their careers. This was the side of education and culture. After services at my grandparents’ church, where much fuss was always made over “the minister’s grandkids,” I remember loving nothing more than coming back to the parsonage where my Grandpa would put records on the stereo to play as Sunday dinner was getting ready. Sometimes Bach, sometimes Herb Alpert, later even Jesus Christ Superstar, I would sit and play games or read near those speakers – unless it was Bach. Bach always made me happy, made me want to move. The direct line from my experiences those days and the loving family that brought me those opportunities to where and who I am today has always been clear. It is safe to say it would be evident to anyone who knows me and had the privilege of meeting all my relatives on that side of the family.

My relationship with the other side of the family was always much muddier, in many senses of the word. This side had generations of sustenance farmers in the family tree, Scots-Irish in the New World from before the Revolutionary War, always moving west just this far ahead of civilization, scrapping to make ends meet and making do or doing without. This was the side that had a farm that had been in the family since before Illinois was a state. The family cemetery was a genealogy lesson: Conley, Fields, Davis…. Electricity had come to the farm, yes, but there was still no telephone and still no running water. We didn’t go to a bathroom when we visited the farm; we went to the luxurious outhouse with two, count them, two seats! Or, as my grandmother used to say, we went to “visit the Joneses.” Why the Jones’ needed two seats in their home I never knew. There was no faucet anywhere of course; we pumped the water from a cistern just outside the kitchen. We always had to be careful for the mud-daubers (wasps) that lived just inside the spout! Some cooking was done in the kitchen; some was done over the woodstove.

The farmhouse had four rooms: the main room, which also had a high metal bed for guests, a front bedroom that was also used for guests, the kitchen, where my grandmother slept on a folding cot, and the back bedroom where my grandfather stayed and where he stored his rifles.

When my sister and I would stay at the farm for a week to give my parents some time alone, my grandparents would pump water from the well one bucket at a time, then they heated it on the woodstove in the living room, then they poured it into the big galvanized metal tub. Grandpa washed first, then Grandma, then me (or my older cousins first if they both were there – then me), then last of all my little sister! I remember that cloudy, soapy, dirty lukewarm water as if it were yesterday. How I hated it! But I did learn that the secret to bathing in the country is not so much to get clean as it is to stay less dirty.

We went fishing at the farm. Once when I was eight or nine, I got a big snapping turtle on my line. I fought it and fought it all by myself, then finally landed it. The grownups had to take over then, as it was big and dangerous. They put it in a big rusty metal trash barrel, and they put the one my cousin had caught that very same day in another. I think a neighbor came over and shot them so that he could eat them with his family. Our family did not eat turtles, but I knew my grandfather had eaten squirrels from time to time. One learns to use the resources of the land one inhabits when resources are adequate and money is scarce.

I walked in the woods, got stung by wasps and bitten by ticks. I went exploring; I especially liked hopping over the creek where it was narrow near the bottom of the pasture, and I liked hunting for wild raspberries in season. The honeysuckle always smelled good. Dad could do a quail call so good that the birds themselves would answer and sometimes come close to him. I liked going with Grandpa and my Dad to cut down trees in the woods. I knew they would go into the woodstove to keep us warm in the Winter after they had seasoned. “Wood warms you three times: once in the cutting down, once in the splitting up, and once in the stove,” I remember being taught.

How grand the Fall was! It was persimmon time, and we learned how to tell just how mushy the persimmons had to be before they were any good to eat. We learned to split open their seeds to forecast the weather: inside the seed was always a shape like an eating utensil. A knife meant the Winter would have cutting weather. A spoon meant you would be shoveling snow all Winter, and a fork meant the Winter would be mild enough to be able to pitch hay outside in the middle of December. We learned to forecast the cold and snow by looking at the bands on wooly worms. We learned that thunder was “God’s tater wagon a-rollin.’” Of course at nine and becoming a well-educated small town boy, I rolled my eyes at such ridiculous folklore and superstitions. But at least I was smart enough to learn them, too, thank goodness.

Sometimes the clay fields grew corn, sometimes beans – they were just never much for making money. Grandpa kept cows in the pasture for neighbors from time to time, but Grandma was deathly afraid of cows, so usually there were never any. Grandma went to her grave without telling any of us the story of why she was so afraid of cows.

By the time I was growing up, the farm was really mostly a hobby farm. All of us including my grandparents came to visit from time to time, and this is exactly what happened this Fourth of July.

I didn’t want to go then, really. I didn’t like the farm then. I hated the backwoods Ozark dialect, the boring long days of waiting for nothing at all to happen. I hated the same stories over and over. I hated the country music on the radio and hearing my Grandma tell my Dad who in town had been sick and who had died and when and where they were buried. Mind you, I didn’t hate the Moon Pies or the walnut candy or the many other stale southern treats that were waiting for grandchildren whenever we came! But after I had scarfed down my share and more of the candy, I was back to moping and wandering, wondering why we had to come to this stupid old farm and live this way with no television and no newspapers and months old Readers’ Digests. What would my friends in town think if they knew I had to use an outhouse?!

This Fourth was a little different, especially to a child fascinated by numbers and by history. The country would be 199 years old; the Bi-centennial was just around the corner. I would be ten years old soon, two whole digits in my age, like a grown-up! This seemed like a pretty special day, not least because some of our more distant relatives and some neighbors were coming to celebrate with us.

My Grandpa had traveled to Indiana to buy fireworks (not a big journey, just across the Wabash from their home in town) for the occasion. I was indignant: fireworks were illegal in Illinois! What if the police came and arrested us all?

I forgot to worry about all that when David down the road brought his team of white horses hitched to a hay wagon. He pulled us down the long farm lane and down the country road. We all sat on the bales of hay and waved and laughed, mainly at each other, since nobody much came down the road that day – or any day, really. It was just us and the measured clip-clop of this beautiful team of horses – another memory that I will carry with me for a lifetime. This part of the day I would not have cared if my friends from town saw! I wished they could see it, in fact. Wouldn’t they all be jealous?

When we got back, Grandma was already at work preparing a Summertime feast: fried chicken, green beans, lima beans, corn, potatoes, Waldorf salad, and watermelon and homemade ice cream for dessert, along with those sugar wafers that are vanilla, chocolate and strawberry, a personal weakness of mine. The women gathered in the kitchen and living room to work, and cook, and talk and gossip while the men and children sat outside the farmhouse. Outside was a stoop as well as a swing between two trees: the older men took these seats and the metal chairs, the younger men got folding lawn chairs, and we kids stood around or sat on the ground.

Then the storytelling started. This branch of the family was blessed with the gift of storytelling. And mind you, the cast of characters present that day would give enough stories even without the truth stretching that always went on at such occasions. I had a great-uncle who had made a fortune in oil and went around in a three-piece suit shooting foxes from a jeep. I had a great-aunt (one of my most beloved relatives) who left the farm at a very young age to go alone to New York City and ended up an executive secretary at Texaco who learned to love opera and the New York Yankees. The former was bizarre to my grandparents, but the latter was well nigh unforgivable. We kids sat and listened to the stories and watched the cast of characters before us and laughed until our sides hurt, when we weren’t out looking for crawdads in the creek or running out to the ponds to look for fish. The girls wore bonnets and the boys straw hats at the farm. I loved the smell of a good straw hat; if I was lucky I got the one with a green plastic visor brim before anyone else laid claim to it.

There were too many of us to fit in the farmhouse that day, so we ate in the yard at a big table laid diagonally – or we children sat on the ground or at the stoop if need be. We ate and we ate; and now the men and women got to tell their same stories, this time to each other. The kids got to listen again, to learn how to time a joke, finish a phrase, give a narrative. Mostly, though, we learned how to eat a watermelon with or without salt, how much faster you could eat homemade ice cream without getting a headache, and how to sneak more sugar wafers when your parents weren’t looking – grandparents don’t tell.

That night when it was dark enough, my Dad and Grandpa pulled a big corrugated metal sheet to the far end of the side yard and began lighting the fireworks. They were nothing big, only big enough for a nine-year-old who was just starting to learn his adolescent know-it-all behavior to worry about the consequences and the weed of crime bearing bitter fruit. If I could talk to that boy now, I would tell him not to worry and just to enjoy the day because it would never come again. But of course, that was exactly what all the adults were saying then; and of course it was the stupidest thing that boy had ever heard. What do these law-breakers know about the future when they can’t even manage the present?

Of course you see where this is going. Decades later, I am the teacher I seemed destined to be even then. Music is a vital part of my being; Bach still makes me want to move. Ancestry and primal memories are powerful draws, after all. But now, the lessons of all my ancestors have come full circle. I am hiking about the woods and fields, living off simple foods, washing in the rural fashion from cups and basins with water drawn from wells. I know how a sustenance farmhouse is laid out; it is the same here. Crops and their values, the seasons and the weather are things I understand not just from books but by sense. The names of birds and trees and the ways they can teach us of our world if we just take the time to notice them and learn their signals are all a part of my heritage, too. Rural protocol is not so different here than it was there. I certainly know how to use a farm toilet! I know the value of repetition in an oral tradition, and I understand the concern for life, death, sickness and health. I can listen to a good storyteller, and I can glory in the power of a great folk song well and simply sung.

With this trip, I feel I have in good measure at last reconciled the parts of my heritage that I had always felt to be contradictory. They were the same music all along – I just didn’t know how to listen with both ears at the same time. A nine-year-old boy with the first inklings of adulthood learns how not to listen, how not to learn – the painful yearnings for willful ignorance that adolescence brings to the all-too-open and trusting mind of the child. It is this yearning that turns us into single-minded adults, determining what we will and won’t do, what we will and won’t see or imagine, what we will and won’t care about. It closes our minds to perceived present irrelevances and to possible futures even as it prepares us to approach our lives with purpose.

Now I have a second chance, a chance to live the lesson I have learned in Africa, honoring my ancestors while daring myself to do things neither they nor I ever experienced before. Once again there is this chance to live as a young child, to be nine again - to be even younger still. Maybe I can be nine for real and for good now, with all I have learned. This time, I can recognize the familiar in the utterly foreign and the undying truths in a life led simply. Most of all, I can celebrate right now where I am, even as I hold dear those who are not with me today, for whatever reason there might be for each.

Happy Independence Day.

The overgrown school of Matepwe The overgrown school of Matepwe SURPRISE!! As I had predicted might happen, I am back early from this most recent trip - but trust me, not without stories to tell! But all in good time... I will continue where I left off.

JUNE 13: Because of the forgotten tent, Mssrs. Joe and Marcos have been staying in the front room of the nduna’s house while in Mcondece, and I have been in the tent in the front yard. I am never concerned about my possessions when camped in places like this; nobody would ever dare touch anything on the property of an mfumu or nduna.

After breakfast and what seemed like an amicable meeting with the choir committee (though not all their problems were solved), we began the hike at 8:30. It is part of local custom for members of the host family or community to carry at least some of a visitor’s burden part of the way as they leave. Here, people from the village carried our packs for the first hour and a half of our journey this time! The weather was warm but pleasant and dry, this being an intermountain climate. I was really enjoying this hike on the flat path, which made it easy for me to take everything in without being overly concerned about watching my step.

We reached Matepwe before noon. I would estimate about one-third of the houses were deserted, but there were plenty of people around – nothing like the “abandoned village” we were told we would find. We took a small detour to the school and found it unused, with weeds growing all the way up to the schoolhouse. When Joe saw this, he wanted to find the chief to ask him if maybe the Trust could take the iron roof to distribute to other villages who needed roofing materials. His concern was that if the roof was not removed soon, a brush fire could happen any time in all the dry weeds. This would melt the roof and render it unusable. By the sort of coincidence one comes almost to expect here, a young man in his teens or early twenties was ahead of us on the path. He told Joe he knew where the chief was and would take us to him.

A slanted view of the mfumu of Matepwe's home (taken on the go). Note the pergola to the left and the geometrically decorated home on the right. A slanted view of the mfumu of Matepwe's home (taken on the go). Note the pergola to the left and the geometrically decorated home on the right. The chief was working in one of his fields. To get to this field, we had to walk down an incredibly impressive avenue of sorts – a path of banana trees that stretched in a line for about a quarter of a mile or more. On the left side, the trees then gave way to a huge sugar cane field, while the banana trees on the right continued to a marshy river. This must have been the same marshy river in which I had gotten a boot wet earlier in the day when trying to jump over it. I was happy to give my boot a chance to dry out while the chief and Joe talked.

Apparently the village is not abandoned, although most of the Yao people in the village had left. This would be another topic for a blog post, but history in this region has caused the Yao and Nyanja to ebb and flow in their population and amount of space they occupy. Also for reasons of history, the Yao have their own language and are Muslim, although their practice of that faith is considered “folk Islam” because it blends elements of their former traditional beliefs. In this region, if the majority in a village is Nyanja, then Nyanja laws are observed and the chief is Nyanja. The reverse is true if a village is majority Yao. From time to time, one group or the other may simply pull up and relocate. That seems to be what happened here. The reason might have been concern over the elephant damage in Mcondece or not. The chief said there was no such damage in Matepwe, so that seemed unlikely. Nobody really seemed to know the reason.

The reason the school was closed was a very different reason than we had been given. In another village on a previous trip, we had met a teacher who had been at Matepwe. It was he who had told us that the village was nearly abandoned. Now we learned from the chief that what had actually happened was that this very teacher had been caught in flagrante delicto by a villager when he walked into his hut and found this teacher and his own wife in bed together. After personal forms of justice had been meted out (I didn’t want to hear the gory details, since I have heard what is done in other such cases), the school committee then voted to impose a substantial fine. Recognizing his future career in Matepwe would be a bit –shall we say - compromised, the teacher requested a transfer, which was granted. The other teacher saw a future of months living as the teacher in Mcondece was currently living, teaching all the children in all grades. Deciding this would be too much to bear, he simply left. Thus, no school. Some families relocated when school closed, and of the remaining families, none wished to be in the choir. Thus, no choir.

The hope, the mfumu told us, was to begin school again in January with the start of the new school year, and the chief was working to get two teachers in place. He produced a list of school-aged children in Matepwe: there were 187 names on the list. The school stays! Joe told him of the overgrown weeds and asked if a committee could be formed to clear them before the roof was destroyed. The chief said he would indeed take care of it.

As we were leaving, the mfumu had the young man we met on the path go into the sugar cane field. He cut nine giant canes for us to take along with us. He then carried one of our bags as we resumed the hike. As he left to continue his own errands, Marcos gave him one of the canes.

We continued our hike until we reached this mfumu’s home. We would have lunch here before continuing to Magachi. Once again I had a chance to see how much more fertile these villages are than those at the lake, with crops I had not seen much before such as fruit trees, rice (this was in fact rice harvesting season) and sugar cane. We had some of our sugar cane for lunch. I sliced my finger with the sharp knife, but I washed it with water from my water bottle and took out a small packet of Neosporin from my first-aid kit. Finally I bandaged it. Since it was a small enough cut to be treated in that way, I figured it should be fine.

Mr. Joe in the red cap and Mr. Marcos nearest the camera - on the trail. The man in the distance is one of two university students from Maputo carrying their backpacks on their heads and traveling the villages doing health surveys and education. Mr. Joe in the red cap and Mr. Marcos nearest the camera - on the trail. The man in the distance is one of two university students from Maputo carrying their backpacks on their heads and traveling the villages doing health surveys and education. Before we left, the chief came back from his field and joined us temporarily; we offered him some of the hot tea Joe had made at the amayi’s fire. We had a pleasant chat as we ate sugar cane and drank tea. He told us from his house we should reach Magachi in another hour and a half. I was a little sad to leave a village without working with a choir, but there was nothing to do about it. We picked up our packs at two in the afternoon as the day began to cool. On to the next stop.

Mr. Joe presenting school supplies to the standing students of Level 4 Mr. Joe presenting school supplies to the standing students of Level 4 Surprise! I am still here; we are not leaving until tomorrow, after all. Mr. Joe has been ill and away from work. We will use today for preparation of supplies and for research for me, since these villages have other tribes, languages and religions than I have worked with thus far. Thus, there WILL now be a hiatus in my posting. See you in a week!

JUNE 11 (continued): After turning into the dooryard of the hut where we would stay, we sat in the shade of the hut of the nduna. The nduna is second in command in a village. He is selected by the chief based upon his merits as an advisor, so this position is not hereditary. We had stopped by the mfumu’s house on the way, but Mr. Joe explained that he lived a little too far out and had too little access to water to make it possible for us to stay there. This hut was built in the fashion that seems more common in the inland villages. The lakeside villages appear to use bricks or grass more predominantly for walls, but here the walls are sturdy bamboo sticks laid horizontally and then covered with a thick layer of mud that dries like cement. The mud can be of different colors depending upon where it was obtained, so each hut can be decorated in different colors and geometric designs. I like this style very much, as each home is individualized and seems to say a little bit more about its family than do the other styles. Sometimes families with children have the sides of their walls covered with schoolwork and drawings, like a giant chalkboard. I especially like those houses. I am very surprised by this inland valley. I am more accustomed to the valleys of the Rocky Mountains, where rain shadows generally prevent good conditions for crops. These mountains clearly do not have that same effect, as I can see that there is a wider variety of food grown here than by the lake. There is a lemon tree growing in the yard among other fruit trees. Joe picks some green lemons and we each take a half to eat. It is surprisingly good – or perhaps my tastes get modified when I am out in the villages. Mr. Marcos had cut two canes of sugar earlier in the day, and they cut some of that off for me to try as well. I really like it, especially how much liquid is inside along with the sugar. You chew and chew the cane sort of like a fibrous chewing gum until all of the sugar water is gone, then you spit out the remaining plant fiber. Only after my lemon half is gone does it occur to me how fantastic it would have been to eat the lemon and chew on the sugar cane at the same time! I hope I will have the opportunity to try it some time. The nduna invited us to lunch around 2:30: cassava nsima with goat and usipa. The meal is of course generous and unexpected, but I believe it has been warmed over from the earlier prepared lunch and so is a little dry and hard to eat after a long, dry hike. I manage a piece of goat and two-thirds of a loaf of nsima. I actually like nsima a lot, both corn and cassava; but I find it expands logarithmically in my stomach. How natives here can manage a full loaf or a loaf and a half is beyond me. Still, because I never eat a full loaf, my travel companions always assume I don’t like it, and then despite my protestations they go to the extra trouble of preparing spaghetti or rice for me. Such will be the case once again on this trip. This family appears to be quite prosperous: the farmland is lush, and the chickens and baby chicks are too many to count. I do count at least fourteen goats in his herd, which is extremely impressive: families are doing better than most if they have one or two goats. In addition to the lemon tree, there are other native fruit trees I do not yet know growing in the dooryard. There are three compost piles, which I would later learn were a direct result of training from the Manda Wilderness Farm Project. I can see already that there are at least a few farms inland operating on a vastly different scale than anything I have seen thus far. Around 4, we go to the church to hear the choir at the invitation of the choir’s chairman. It is about a mile away, and on the way the chairman shows us elephant damage where the herds have trampled some grass near the river. It is very rare to have crop damage from elephants already at this time of year, and the locals are worried. Obviously families do not have enough cassava to share with a marauding herd of elephants. It takes very little damage of this sort before conflicts between humans and elephants begin. Often in this region it results in families leaving the village; this is what we have heard may already have happened in Matepwe. As we approach the church, it becomes clear very quickly that we have entered another league entirely where choir preparation is concerned. Upon hearing our approach, the choir has actually left the church and hidden from sight behind some nearby huts. As we round the corner and see the church for the first time, we hear them singing nearby but cannot yet see them. Twenty-five singers approach in two lines, dancing and singing as they go. They form a human passageway between the church and us. At this point, the choirmaster appears at the far end of this passage and bows to us, then comes to take me by the arm in the local fashion to indicate we should pass through. The choir is singing “We are coming; we are coming slowly. We will be there soon.” As we go through the line, they turn in our direction but never look directly at us. After we pass and enter the church, they continue the song as they merge lines and dance into the church single file, taking their places for rehearsal. I found this entire welcome ceremony intensely moving; there is not a doubt in my mind that I will carry this moment with me for the rest of my life. Together, without any words exchanged, they performed three excellent songs while dancing, not seated as is usual at the beginning. Clearly this “rehearsal” was a planned welcome performance, and they had already warmed up. Likely they were informed soon after we entered the village. I listened intently to learn what I could about what they might want me to work on, since this would be a different sort of work. The songs had minimal sharping and were very coordinated. After three songs, the choir sat down. It was time for speeches. The choirmaster welcomed us, and then the chairman gave his welcome. Everything was in a very formal, deliberate style. Joe chuckled because the chairman was addressing me as “ madala,” a word I did not know: “We are very honored to have the madala with us to teach us all he can from his knowledge.” Joe tells me that madala is a highly respectful, honorific title for an old man. Terrific. Next comes Joe’s introduction of me. I am startled as I rise to make my speech, because the choir claps loudly in unison when Joe finishes. For the musically inclined, the rhythm was two dotted eighths followed by an eighth note, then a quarter note sharply performed with extra accent. I then rise to give my introductory speech in Chinyanja. The choir responds with the same rhythmic clap. Clearly this is their way to applaud or indicate thanks or assent. Everything they do is prescribed and choreographed. After the formal speeches, the choir sings three more songs, this time seated, thus inverting the standard rehearsal format I have observed thus far. We then take our leave, the choir applauds rhythmically together again and we go, as they remain seated silently. Tomorrow should be fascinating. JUNE 12: After the previous days adventures, I slept very well. We are in a high mountain valley now, so the night is the coldest I have experienced thus far. I estimate it might have been in the upper 40s. “ Nkozizira” becomes a term I will hear frequently on this trip: “It is cold.” After a breakfast of rice and beans, we first go to the school. Manda Wilderness has received a gift of pencils, colored pencils and paper from a generous donor, and Joe has asked me to take photos of their presentation to send back to this person or foundation. There are two rooms in this schoolhouse. Currently there is one teacher in town. Mozambique hires teachers for schools, but they do not receive their first salary for three months. At that point they must make the lengthy and inconvenient journey (four hours on chapas IF there are no stops or mechanical problems) to the provincial capital of Lichinga to collect their paycheck. After this initial trial period they must make this same paycheck journey every month of their stay since there is no postal service here. In order to ensure that the national language of Portuguese is properly taught, teachers are often assigned to communities outside their tribal home and language to force the use of Portuguese. Of course, this also means these teachers are unable to speak with the people in the village until they have been there a while. Frequently, teachers leave for their first checks and simply never come back; it is just too difficult an adjustment. This teacher is from the area, however. It is believed that the other teacher is likely to come back. In the meantime, school goes on. This teacher will take the five grades himself each day. When we enter the first classroom, half of the children stand in unison and remain standing as long as we are there. “ Bom dia, senhor professor!” they say in unison to us: “Good day, Mister Teacher!” Clearly they have learned this greeting as a rote response to their teacher entering the class, but they do not know what it means. The teacher explains that we are not the teachers, so they should only say the first part. He asks them to try again. Rote learning is not that easily removed from the brain, though, alas. “ Bom dia, senhor professor!” they say a second time. We all laugh, and Mr. Joe begins handing out school supplies as I take pictures. This classroom has the rather odd combination of first and fourth grade. It is the fourth graders who are standing; the first graders apparently are not expected to do so yet. Once the supplies have been passed out and the pictures taken, Joe takes them right back from the children. School supplies are much too precious to entrust to children. The teacher will keep them at his home and distribute them each morning and collect them at the end of the day. He will now spend the rest of his morning shuttling between the 1 / 4 room and the level 2 children in the other room. In the afternoon, level 3 will be in one room and level 5 in the other. I wonder how he manages. At least Mcondece is a fairly sparsely populated village, so class sizes are much more manageable than the hundred or so students in a classroom I have seen in other schools.

Mr. Joe with the seated students of Level 1. The valiant and currently lone teacher of Mcondece is looking into the camera. These nice desks are VERY uncommon in the villages, by the way. Mr. Joe with the seated students of Level 1. The valiant and currently lone teacher of Mcondece is looking into the camera. These nice desks are VERY uncommon in the villages, by the way. The photo op finished and proper leave taken of the teacher, we go to the church for rehearsal. We wait for just a bit, but not long. A different member of the choir than the chairman or the choirmaster is berating the members. Some of the adults respond while the children sit still, eyes forward. Joe laughs because the adults are saying they were late to rehearsal because it was too cold this morning; they had to wait for the sun to come up to get ready. The chastised adults have it better than the children, though! The choir has an appointed choir disciplinarian: an older tenor stands outside with a stick. As children come late, I can just barely hear him outside asking their reason, telling them it is not an excuse, and then beating them soundly with two raps across their bottom. One older girl enters the church rubbing her sore backside. Beatings of children are not at all uncommon here; it is one of the difficult things for me to witness in the villages. Only one child, a boy, escapes this fate. After a brief discussion, he is allowed to pass untouched. I wonder whether his excuse was really good or if he is the child of an important personage.

Inside, rehearsal has begun. From time to time, a man next to the disciplinarian touches his arm, jerks his head toward the door, and the swift arm of justice rises and leaves briefly. Shortly after, he re-enters just after a child with downcast eyes. We continue with our songs of the Eternal Love of God. I am discovering that this choirmaster, Mr. Jaime, is a bit vague with numbers. He announced (everything is a formal announcement here) that they would perform two seated songs as a warm-up, but they actually sang four. This choir is clearly ready for more advanced training in matters of breathing, posture, movement and tongue position. I haven’t done much work with tongue position in many of the villages, but this group appears ready to discuss this. It is unclear to me though whether they fully understood the concept, as it appears to be difficult to translate into Nyanja.

After a couple of songs with dance, in which I make some minor corrections, we begin work on “Chauta.” They pick it up quickly, naturally. They are a bit confused and perhaps offended that they may only sing the refrain at the festival and that they must pick one or two singers to perform the verses. I explain that some choirs are new and were only able to learn the refrain; we do not want to embarrass the new choirs by showing them up with how much more quickly some groups were able to learn. I can tell by the group’s faces that they are not particularly concerned with these inconvenient newcomers and want to sing the entire piece whenever they do it. I reiterate the plan firmly but politely. I think we got that cleared up, but I am not entirely sure.

When the choirmaster hears that I will be making a video of their performances so that they can see them for the immediate feedback, he announces that they will now perform ten songs (!) the remainder of the morning, from which I can select and later record the five best for the afternoon session. It is both refreshing and a bit disconcerting to rehearse with an ensemble that is so direct and formal with its intentions and wishes. I have become accustomed to a much more roundabout approach by now. I have to recalibrate! I agree to this plan and they begin. “Ten songs” actually turned out to be five; I select three. I am certainly not going to be in the position of selecting only the two songs for them to perform at the festival, and then take the blame if they don’t go well! These three songs really are the most rhythmically and melodically complex that I have heard so far, although not the most complex in terms of dance. Two pieces in particular I am really looking forward to hearing again: one with a solo trio (!), and one with a gospel choir-like repetition section building from the sopranos down as the choirmaster takes a spirited solo.

At lunch we return to the nduna’s house. As we pass people and greet them, I am noticing that people are even more formal here than they are in the lakeside villages. People always rise to speak in formal situations, with much thanking and courtesy. There is near universal use of the ultra-formal address in greetings. Normally, Chichewa and Chinyanja use “iwe” forms for children, animals and intimate family and friends, and the plural “inu” for other situations. So far this is like many other languages. There is a third form, though, which is “iwo,” which actually means “they” under normal circumstances. Thus you are addressing someone “How are they?” “Do they want to do something…” etc. In studying the language, books said that this form was more or less obsolete, but I am here to testify that it is in fact alive and well in these more remote villages. Needless to say, this style takes some practice to get the hang of, to look directly at someone and address one person in the plural third person. Try it in English! I hope I don’t make any bad faux pas as I learn this new form of address.

The afternoon session was spent mostly taking and reviewing videos. Here the ensemble’s Achilles Heel was revealed. The group is so trained, so regimented and rehearsed, that any form of audience causes their adrenaline to go way up. Their tight disciplinary system causes them to freeze with worry that they might do something wrong, especially on video. Of course this means they begin making mistakes they did not make before, including the sharping I have heard everywhere else but not here. I remind them of the low breathing work we have done. We also talk about facial expression, especially expressions of happiness or joy. It will be interesting at the festival to see if any of this work transfers into their system. We add movement to “Chauta,” then the choir sits in preparation for the concluding speeches and prayer. I first ask if the group has any questions. The women and children sit, eyes forward, while the men huddle and whisper for a brief conference. The chairman stands and clears his throat, then looks me in the eye. “Palibe mafunso,”he says then sits down – “There are no questions.” Then we pray, give our formal speeches of farewell, the choir claps rhythmically, and our official time together is over. Five people stay to work on the solo section of “Chauta,” so apparently the small choir part of the morning’s explanation did make sense to the group after all.

Upon parting, the choir chairman hands Joe a letter with a list of demands they would like Manda Wilderness Community Trust to meet. Joe schedules a meeting with the choir’s leadership committee for the next morning to respond before we leave.

We head back to the nduna’s compound, past the elephant damage, past the bridge where women are washing their clothes in the river. Dinner is goat again, as well as chicken! It is certainly not dry this time; everything is delicious and simply prepared. Does this family have meat every night? Surely not.

Tomorrow our journey will take us through Matepwe. If there are any people left, we will check to see if there is still a choir and if it wants some training. Otherwise we will continue to Magachi.

News: I am scheduled for an eight-day trip to the most remote villages, beginning tomorrow. These two villages do not yet have choirs, so we will be starting together from scratch. I may or may not be away for the full eight days. This seems like a good entry to leave up for a time. After this trip I will have visited all the villages in the Manda Wilderness, though I still have one choir left to see: ironically the one closest to the lodge, Mala, which had to reschedule due to school conflicts.

JUNE 11: This day began early, with the slow boat Miss Nkwichi leaving the lodge at 5:30. Supplies were arriving from Lichinga, so the boatmen would need to use the large boat in order to bring the fourteen car batteries used for solar power at the office as well as all other groceries and office supplies. All these will have to be transported by hand from the truck at the top of the hill to the boat at the bottom.

There was a big windstorm last night (the dreaded kumwera wind), and the waves were extremely high. At one point, the boat crested an eight-foot wave and plummeted. I knew the boatmen were experienced, but I had to turn to them and make a slack-jawed expression as a “joke.” They laughed hard, and I figured if it didn’t bother them, it shouldn’t bother me. I was just grateful I don’t get seasick.

We picked up my guide for the day, Mr. Marcos, in Utonga. Marcos is traveling with us because with the length of time and distance of this trip we have many supplies and need an extra person and backpack. It will be interesting because of his part of the language “triangle” here. The lingua francas here are Nyanja, English and Portuguese, but it seems nobody speaks all three – only two at most. Thus it is that I speak English and beginner-intermediate Nyanja, but extremely limited Portuguese. Marcos, on the other hand, speaks Nyanja and Portuguese, but extremely limited English. This is how it goes here, and one switches languages seemingly at random, but actually based on a complicated system based on location (English is more prevalent on the lakeshore but nearly absent inland), race (almost nobody speaks Nyanja to me upon first greeting) and age (children learn Portuguese in school but only by rote and with limited understanding). It doesn’t take long to get the hang of the whole affair, but this is the first time I will be traveling for a while with a companion who does not have much of the English side of the triangle. It should be interesting.

From Utonga, the lake inexplicably calms down – the lake is notoriously fickle like that. We dock at Cobué at approximately 7. Because the boat will be there the whole day as they wait for the supplies to arrive, they put anchor at a different spot than usual, a rocky shallow with no natural docking point close to shore. We have to jump in and wade to shore. I am glad I packed my sandals so I could wait for my feet to dry before I put on my hiking boots.

From the shore, we hike uphill to the waiting spot for the chapa. Chapas here are the size of box trucks but with a pickup truck bed in the back. This back area is where the cargo is carefully placed and the people get in as best they can. The waiting spot is just outside the porch where I have watched the two tailors working so many times before, but their store is not open yet this morning. There are many people sitting at the porch, so I grow a bit nervous as to how many of us will be in the chapa. After waiting an hour, the truck pulls up. As it turns out, many people are simply there to make cargo transfers or just to gossip. Once people coming from points north unload from the truck, a very few people put cargo in, including one man who throws in a backpack with a live chicken tied to it. I am feeling lucky at the paucity of passengers! Our backpacks are whisked away, but I am told the chapa won’t be leaving for a while, so there is no sense our getting in at the moment.

Marcos and I have some errands to run in town anyway. The Farm at Nkwichi will be having a luncheon for staff and volunteers this coming Sunday, and Lily has asked us to pick up what we can from 2 kilograms of rice, a kilogram of beans, a half kilogram of salt, onions, and five green tomatoes to ripen over the week. We are also to look for cornhusks [gaga] that serve as supplemental chicken feed in the region. Gaga is a very rare and valuable commodity this time of year, and rumor had it that there was a large supply in Cobué at the moment. As it turns out, rumor was mistaken.

Next errand. Marcos understood that we needed onions, but there were no onions at the market. I also mentioned matimati [tomatoes], but he did not seem to understand me and was not looking for those. It was just as well, as I could see there weren’t any. Many stores were still closed, but we did find a vendor who had rice, though nowhere near as luxurious an amount as two kilograms. We cleaned him out of rice and beans, and he charged us 160 meticais. Lily had given me money, but unfortunately the lodge only had a 1000 meticais note (about thirty dollars). I knew trouble was coming when I handed that over. “Pepani" [Sorry!] I said. Ah, no problem, he assured me, but he and his family could be heard scouring the house to find money for change. We had already wiped him out of rice; were we going to take all his change, too? He brought back part of the change while the family continued to look for the rest, so Marcos took the change we had to go and get the tomatoes. I had to explain that they should be green tomatoes, but I had forgotten how to say “green” in Nyanja (some colors are verbs, and green is one of them: “to be green,” which must then agree with whichever of the sixteen possible noun types and numbers is relevant), and I didn’t know the Portuguese word for “tomato.” I would just have to resort to PortuNyanja: “matimati verdes!” I called out as he disappeared into another store. My vendor soon returned with the change: no meticais, only kwacha. Shortly thereafter, Marcos came back… with five cans of tomato paste. I had no idea how to explain what we had actually needed or how much, so I gave up. Maybe somebody at the lodge needed tomato paste. We gave our goods to the boatmen to take back with the rest of the supplies.

While we were running errands, the chapa had gone to Julius’ beach and had come back with many bags of rice in the back. These are fine as places to sit, so that seemed well and good. As we came back up to the tailors’, the chapa went down the hill where we had just been and pulled up near a different store. Here they got some more unwieldy cargo of unknown items covered in tarps. Now it lumbered back up the hill and seemed ready for passengers.

At that moment, people began appearing as if from nowhere, thrusting items up toward the man who was packing the chapa. He had a rope dividing the back into halves, and he was putting all the cargo in the back. Clearly the front was going to be for passengers. I began to panic. More rice bags, large sacks of clothes, suitcases, a head- and footboard for a bed, all these and more got loaded and re-loaded. I was very relieved to see that our backpacks always made their way back to the top of the pile, since of course my pack had my solar collector inside it, as well as my iPad, tucked inside the solar bag for some protection.

Next, it was time for all of us to get in. I do mean all of us! Three women with their babies took the floor bed, as did an older man who must have been at least seventy-five and as thin as a rail, dressed up in an old suit complete with bright purple shirt and a tie. The floor bed seemed to be the place for women, infants and the elderly. One of the women with a baby also had her own grandmother of about seventy gripping her arm tightly, a chitenje covering her face either from fear or to avoid carsickness. She would stay in that exact position for the duration of the ride. The men then began to climb on, all avoiding the cargo area as much as possible, sticking their feet into the floor bed under the women but sitting on the sides of the truck or carefully on the edges of the rice bags. I was sitting on the edge of the truck on the driver’s (right hand) side. Last to arrive was one of the few overweight people I have witnessed here, a middle-aged woman who wedged herself into the very center of the floor bed. The other women pulled their knees up and the men including me simply allowed her to sit on our feet. She had to endure a few mildly disrespectful joking comments, which she simply chose to ignore. There were twenty-three of us jammed into an area half the size of a small box truck. Just as the chapa was leaving town, two more fishermen jumped on the back and climbed in to make twenty-five in all. There was no place for them but the cargo area. One man took a large plastic bag of usipa [a small fish like a sardine that is dried and then eaten whole] and set it right on top of my backpack. Then he put his feet on it, though not his weight. Around 9 o’clock, the driver honked and restarted the engine.

With that, we lurched forward. The first part of the “road” from Cobué is potholed and rocky. Bridges sometimes are at the same level as the rest of the road, sometimes not. The drivers speed up to almost 40 miles an hour when the road allows, then slam on the brakes when they come upon a bridge, large pothole or stray chicken or goat. It is not possible to look forward around all the people to anticipate when these sudden changes in speed might happen; we simply slide into each other from side to side, back and forth. I gripped the edge of the truck with one hand, and the man next to me threw his arm around me to steady himself. I was happy with this because it made me feel less likely to fall off the truck. The man on the other side put his left hand under me for stability. With all the jostling, the old man in the purple shirt had been shoved up against the driver’s cab, his knees literally touching his nose. He simply sat there like that, facing backwards and making no sound. I looked over at the mother with the gripping grandma. Her baby was wrapped in a chitenje, sound asleep. Its head was bouncing back and forth, forward and back. Grandma kept her face covered. The larger woman reached for her purse and pulled out some roasted nuts and began eating. Eating or drinking in public among strangers is extremely rude here; one never knows if others have had anything to eat that day, so it is considered an unseemly flaunting of one’s good fortune. She must have been very hungry to have done that. Needless to say, sitting on the edge of a pickup truck while going over spine-numbing bumps and ruts is – well – uncomfortable for a man. I found the whole experience excruciating and just wanted it to end. I was trying not to look it, but many people were talking about the azungu and laughing. I can only imagine what I really looked like.

After forty minutes of one of the bumpiest, hilliest, stop-and-goingest rides I have ever had, we were finally there – wherever “there” was. It was actually a T-junction of two roads where we were to wait for Mr. Joe to join us from work he had been doing in Mandambuzi. I jumped out as fast as I could, once I got myself extricated from the human jigsaw puzzle. The driver told me he wanted 100 meticais for the two of us. But the merchant had given me only kwacha in Cobué. “Ndilibe meticais,” I said – I don’t have meticais. He gave a disgusted look and said that it would be 1500 kwacha, then – a substantial rise in price, since the exchange rate kwacha to meticais is 10:1. It should have been only 1000 kwacha. Still, there was not much we could do about it, so we ransomed our luggage for the fee. The truck drove off, leaving us at the junction with several bags of rice and two women and two children who seemed to live at the house there.

The women found my being there in the middle of nowhere, really, a source of immense amusement. They were asking Marcos in Nyanja why I had not simply driven my own galimoto [motorcycle or car] wherever we needed to go, and they were doing a sort of driving dance to indicate how I might have driven down the road. Marcos let them know that I spoke Nyanja, which appeared to tone down their dance a bit. “Ndilibe galimoto kapena ndalama,” I said. “Ndipo, ndine mwamuna wopanda nzeru.” – “I have no vehicle nor money, and apparently I am a man with no intelligence as well.” As I had hoped, they liked this reply very much, and we were friends after that.

It was at that point Marcos realized he had forgotten his tent on the truck. There was not much we could do about it at that point, other than to ask the women if they could let the drivers know about it when the chapa returned the next day. They said they would. Now we could only sit there and wait for Joe.

We waited for about an hour as the day warmed quickly; it was almost noon. Marcos told me in PortuNyanjEnglish that we should go look for a bicycle so he could go down the road to find Joe. We went to the first farm down the road where they did indeed have a few bicycles. After the usual lengthy introductory formalities, and the equally lengthy explanation of what had happened that day, why we needed a bicycle and what we would do with it, the family readily agreed to hand over one of their most expensive possessions to two total strangers.

Marcos walked it down their path to the road and was just about to mount it when who should come from the opposite direction but Joe, on a bicycle. He had hiked for two hours from Mandambuzi, had gotten weary and had done exactly what we had done, borrowed a bicycle from strangers. We turned back, returned our bicycle with thanks to the family; now protocol demanded that we explain what had changed our plans and what would happen since our plans had changed. We then walked back to the junction. A small boy of about eight had magically appeared. Joe explained where he had borrowed the bicycle. Yes, the boy knew the place. Go and return it, then, Joe told him. One does not ask children to do something here; one simply tells them to do it and they do it, even for complete strangers. The boy hopped on and began pedaling, a boy unknown to any of us returning an item that might cost upwards of a half a family’s annual salary to people who had loaned it on faith to a total stranger. This is NOT uncommon here at all; how is it that people are more generous and trusting the less they have? We turned around and began walking the other way.

I had worried that the road would be mountainous, but it turned out that the chapa had done all the climbing and that we were now in a wide, flat valley. Not quite road, not quite path, but extremely good for walking. All that worry for nothing. After a three-hour, seven mile hike, we were in Mcondece.

A journey that began at 5:30 in the morning ended at 3 in the afternoon. I had covered about thirty miles by boat, chapa, with a bicycle and on foot, using Nyanja, English, Portuguese and pidgin. I had had one of those small bananas to eat the entire day thus far. In other words, one month after arrival, I had spent at least one day living as does a local resident.

Joe and Marcos pulled off the path. We were at the hut where we would stay in the yard for the evening. This was the village of Mcondece.

A cassava field and farmer's buildings along the mountain valley path.

Caught in passing on a mountain path Caught in passing on a mountain path I interrupt the narrative of this blog to bring a flower. There are many flowers here, which I always find incredible since it hasn’t rained now for at least two months. Though still plentiful, the leaves on the trees are all slowly turning brown and dropping. Rivers are drying up; places I had to jump over on trails going in one direction I can now walk right through coming back. The crunch of gravel on the path is now sometimes intermixed or even replaced by the crunch of dry grasses and brush. But the small wildflowers just keep coming somehow.

I have learned to appreciate and try to commit to memory or pictures the flowers, birds and animals I see whenever I can, because a week later some of them are gone, only to be replaced by a new set of wildlife that only appears that many weeks into the dry season.

This particular flower I have mainly observed in the mountains in the last month, though it can also sometimes be found at lower altitudes. Strangely, it always seems to appear alone in unexpected places. To get this picture, I had to leave my camera out for three hours of a hike, because one never knows when one will see it.

Perhaps the birds carry it in their flight. Maybe the wind carries it where it will. Somehow, though, in sun or shade, it roots itself, pushes itself upward and flourishes. It seems to send its message of hope and perseverance in unexpected, unfamiliar circumstances every time, and it always makes me think of a special place and a very special person who has a particular fondness for daisies.

Happy Anniversary, dear.

View of Chizimulu Island from the top of Mt. Njakwe View of Chizimulu Island from the top of Mt. Njakwe UPDATE: I am back at the lodge again, though I am not sure for how many days. The power is in much better shape here; they discovered two wires that were shorting the system. It still needs new batteries, but we can actually charge our computers without taking them individually to the kitchen building, one at a time! I have also been able to load the missing pictures from the preceding post. Luxury!

JUNE 8: Today I hiked to the top of the mountain near Mango Drift, Mount Njakwe. It is an unmistakable landmark over in Mozambique because it is the place where the cell phone tower is located that serves the islands and the Mozambican lakeshore. Curiosity drove me to go up that mountain since I have been looking across the lake at it for a month whenever I have gone to Cobué. Needless to say, the view is unbelievable from the top – actually almost to the top, not the very top… the very top is a cell phone tower. As always when I am feeling a little proud of an accomplishment, two local residents – older women – are rapidly climbing the same path I just took. One is carrying a huge machete. In Chichewa they greet me and ask me where I have been (a standard greeting question). I tell them I had just climbed the mountain, and the woman with the machete tells me I am a “Man of Power.” We all have a good laugh over that, and they crossed over to the other side of the mountain.

My favorite picture: the choir space (though the choir does not use it) My favorite picture: the choir space (though the choir does not use it) JUNE 9: I went to the service at Saint Peter’s Cathedral this morning. I still marvel at how impressive the church is. I was anxious to get there by the 8 o’clock scheduled starting time and practically ran across the island; the service did in fact start at that time (!), so it was good that I made the effort.

Because it is a cathedral, this was a full service including communion. That meant the service was three hours and forty minutes long. The only difficult part was the announcement portion that replaced the prayers of the people. A man delivered a treasurer’s report that went on and on and on. Several young men in front of me looked at each other and simply got up and left. I stuck it through because I was determined to see the whole service. Everything was difficult to understand because they were speaking very fast and using amplification. Likoma has electricity every day from about 6 a.m. to noon, then again from about 2 p.m. to 10 p.m. In this part of the world, if a little amplification is good, maximum amplification must be just this side of godliness. Add to this that we are in a resonant space, and I leave the volume level to your imagination.

The choir was good, although I do believe there are some I have seen in Mozambique who are at least their equals if not better. The Mothers, however, are quite good. The Mothers Society is a group of women in many churches here. They usually wear outfits that almost look like habits: white blouses or jackets with dark blue skirts and often a white headscarf. They have many roles, not least of which include serving as a second choir and as child disciplinarians. They performed with considerable energy and very good tuning, not going sharp as they sang as tends to happen with most choirs here. They sang during offering and communion; I would have enjoyed hearing them do more.

The cathedral was full; I estimate it can hold a congregation between 350 and 400 people. After communion, though, all the young children who had been in Sunday School came up to the communion rail to be blessed, twenty or so at a time. Next came mothers with small infants. I believe there were a hundred children or more, so that would be approximately five hundred worshippers at the service, not counting infants being held by mothers. The island has eight thousand inhabitants total. The choir finished with a postlude song that I recognized from my time in Chigoma village. There is a fairly standard repertoire of songs that choirs perform, and I have now been here long enough that I am starting to recognize a few of the most popular. I hummed along with them as I left the church.

Another beautiful sunset, Likoma Island Another beautiful sunset, Likoma Island On the way back to Mango Drift I took the western path away from Mbamba Bay. It is a hillier path but more scenic. Two girls about nine years of age approached me. We exchanged names; this is extremely important in the culture here – one’s name is vitally linked to one’s identity. In fact, the question here is not “What is your name?” as if it were separate from one’s being, it is “Your name is Who?” which implies that the knowledge of one’s name shares something of the essence of the person. Their names, as it turns out, are Lina and Alice. Next, as is common here, they first asked me (or rather, demanded) in English “Picture.” Next “Money.” Last, “Balloon.” I don’t know where the balloon part has come from, but this seems to be a universal request from children of this region when they encounter white adults. Once they were convinced that I didn’t have a means to provide any of these things (not least of which was because I told them so in Chichewa), instead of leaving, they befriended me on the way and began quizzing me on what things were in Chichewa. They started with parts of the body, then moved to houses and people, and finally to trees and flowers, which was terrific because I learned some new words in each category and reviewed some words I forgot I had learned. By the time we reached their homes on the western side we were talking away like old friends about school and friends and who lived where. I always enjoy conversing with children because their language is simple, direct, and relatively slowly spoken. I was sad to see them go, as I walked the rest of the way alone along the coast.

This was my last day in Likoma. On the 10th I would return to Nkwichi, retracing the voyage I took four days earlier. I would spend one afternoon and night at Nkwichi, but on the 11th it would be time to go on the next voyage. As I mentioned earlier, this would be my first trip inland. The schedule calls for me to visit Mcondece, Matepwe and Magachi, all villages in the same long valley between mountain ranges; but rumor has it that Matepwe has been abandoned due to crop damage from elephants. I suppose we shall see. I wonder if I will see any elephants….

The view that greeted me. The island in the distance is Chizimulu: "Cheesy" for short. The view that greeted me. The island in the distance is Chizimulu: "Cheesy" for short. I am off to the villages again - this time three villages in five days. Sorry to leave the blog hanging mid-trip, as it were; but there is no cliffhanger; just a trip that was too long to put in one post. I will be back on Tuesday night and hope as always that the internet may be working a little better upon return. We shall see...

JUNE 6: I wake up early, a little worked up that I am scheduled to be on Likoma Island for four nights. Mozambique does not recognize volunteer work, so I am here on a thirty-day-at-a-time tourist visa. It is lucky for us here that Likoma Island is so close – approximately fourteen kilometers, I believe. Most volunteers, then, take this voyage once a month. The boats from the lodge need to have guests on them in order to be profitable, so the lodge cannot afford to transport volunteers one by one. We “hitch” rides on scheduled runs. Thus, I will be going on the Cobué – Likoma run this day when the boat picks up guests from the airport there, but the next guests are not scheduled to leave Nkwichi until the 10th, when I will return on a boat laden with supplies as happened last time. On the bright side, this extended stay does mean that I will be on the island for a church service on Sunday. The cathedral here is very famous, so I am looking forward to that.

On the way to Cobué, we have to pick up and drop off some oil in Mala. As we are leaving from the north side of Mala, a little girl of six or seven tries to push the boat as we are leaving. “Atithandiza,” I say – “She is helping us.” Again this causes my travel companions to laugh; this invariably happens whenever I speak Nyanja. Once again I worry I made a mistake, but instead I am asked how my Nyanja got to be so good! This is the first time someone has asked me about Nyanja, not Chichewa, so I feel as if maybe I have been making some improvement after all. This is encouraging, because lately I have been feeling a little stagnant in my language progress.

As a result of this bit of kindness from a staff member, I am feeling brave when we get to Cobué. The immigration officer knows me by now from the times he has seen me in Cobué, and he greets me in Nyanja right from the start. We conduct the emigration process in Nyanja! In fact, the staff member from Nkwichi assigned to help me through Migração [Immigration] in case there are any problems leaves halfway through to complete his own paperwork for the boat trip. This was a good day if for no other reason than this; I guess I really am getting more acclimated!

The lake was extremely smooth, and we made the crossing quickly. I got off in the “big city” of Mbamba Bay, returning to it about a month after I first saw it. We disembarked by the landmark Hunger Clinic and went to the immigration “office” [stall] near my beloved soap sign. Nobody is there, so we called the junior officers who were having trouble figuring out where and how to stamp my passport last month. They tell us to go to the senior officer’s house about a mile away, which we do. He recognizes us, welcomes me back and tells us he would love to help, but this is his day off and he doesn’t have the stamps or paperwork with him. I congratulate him on his day off and we set off for the junior officers’ headquarters. Why didn’t they tell us to come to them in the first place? Maybe they forgot that they did in fact have the materials. We get to the building where they are… I am not sure whether it was a house, office, barracks or all of the above… and we finish the passport process. They are certainly much more efficient this time around!

After accompanying me down the path and getting assurances from locals that indeed we are going the right way to my “backpackers lodge,” staff from Nkwichi wish me a good stay and head back, since they must run errands similar to the ones they ran the first time I came and must also pick up the guests at the airport. Now, I am alone on a rural path in Africa for the first time. I only ask if I am on the right path once; otherwise I look for the occasional rocks with “MD” painted on them for “Mango Drift” where I will be staying. Some also have helpful arrows painted on them as well.