My tent outside the mfumu's compound. I love the pattern on the home in back! The building on the left is for temporary grain storage.

My tent outside the mfumu's compound. I love the pattern on the home in back! The building on the left is for temporary grain storage. JUNE 13 (continued): Just as the chief of Matepwe had predicted, we arrive at the home of the mfumu of Magachi in almost exactly one hour and a half. The chief here is very kind; his graciousness is all the more impressive due to the fact that neither he nor the choir received any of the letters the Trust had sent. We are essentially walking into his home completely unannounced. Nobody seems particularly disturbed by this, however – least of all the chief. Perhaps this happens on a regular basis due to the remoteness of the village.

Once again, Mr. Joe and Mr. Marcos will stay in the front room of the mfumu’s house, while I will stay in the tent but just outside the compound. This seems to disturb Joe, and in truth it is a little bit of an unusual arrangement here. Though Joe normally stays in this place when he is here, my tent will be near a central path for the village. I really don’t feel any sense of worry myself and assure him I will be fine there. We set up camp. As they go to unload their belongings, the usual crowd of children begins to gather to see my crazy house and funny looking me. I entertain them with some silly dances, which they enjoy immensely. Marcos walks in on my performance. “You are making the children very happy,” he says in Nyanja. The longer we are on the trip and the more comfortable we become with one another overall, the more I have enjoyed Marcos’ company. He actually takes time to teach me the names of things and gently corrects me when I make grammar or usage mistakes, especially in the differences between standard Chichewa and Nyanja. This I really appreciate; how else am I going to learn?

Once again, Mr. Joe and Mr. Marcos will stay in the front room of the mfumu’s house, while I will stay in the tent but just outside the compound. This seems to disturb Joe, and in truth it is a little bit of an unusual arrangement here. Though Joe normally stays in this place when he is here, my tent will be near a central path for the village. I really don’t feel any sense of worry myself and assure him I will be fine there. We set up camp. As they go to unload their belongings, the usual crowd of children begins to gather to see my crazy house and funny looking me. I entertain them with some silly dances, which they enjoy immensely. Marcos walks in on my performance. “You are making the children very happy,” he says in Nyanja. The longer we are on the trip and the more comfortable we become with one another overall, the more I have enjoyed Marcos’ company. He actually takes time to teach me the names of things and gently corrects me when I make grammar or usage mistakes, especially in the differences between standard Chichewa and Nyanja. This I really appreciate; how else am I going to learn?

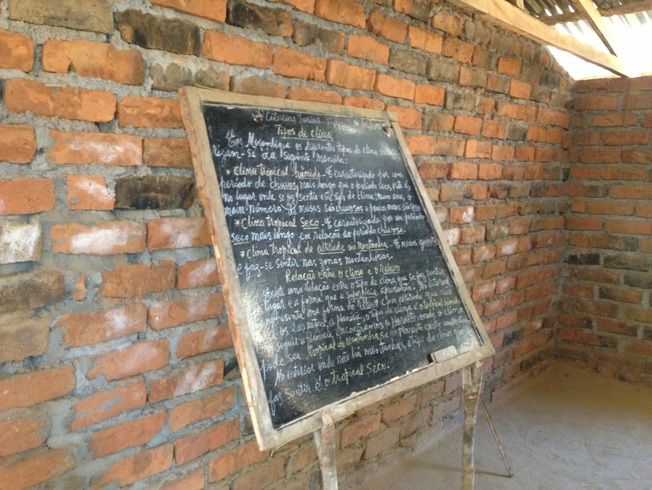

A lesson on Mozambican climatology, neatly written in Portuguese at the Magachi school

A lesson on Mozambican climatology, neatly written in Portuguese at the Magachi school Once again a choirmaster has apparently been informed of our presence as if by magic, and soon we hear the metal pipe that serves as the church bell here calling the choir for a meeting and rehearsal. Magachi is quite far from the action (thirteen miles even from Mcondece), and this is the first time in three years that a choir is up and running here in time for the festival. By 4:30 or so, all are assembled who are able to come, and we have speeches followed by the choir singing two songs seated. We all agree that 9 – 11 will be good for the choirmaster and any adults who can come to meet with me, and then the children will join us after school at 2. The choir is very much younger than most choirs I have seen so far, with many fifteen years old or under. I will need to alter my instruction accordingly.

Tonight we had dinner in the chief’s “backyard,” their walled-in family compound. We do separate cooking from the family over an open fire in the corner. A granddaughter named Maria who also sings in the choir and whom I estimate to be about twelve years old has apparently been assigned to assist us in whatever way we need. Fortunately our needs are few. We are having spaghetti, but the family is having nsima, which always takes a long time to cook. As we are eating and they are waiting, the chief tells us the story of the name of Magachi. Apparently the Yao were in the village first, and their name for the place was their name for the local river as well: Chizulu. They grew mostly beans, however, so the first Nyanja settlers heard the Yao name for beans all the time: Magachi. That is the name that finally stuck. I think it is actually a nicer sounding name and say so. This seems to charm the chief, who appears to have taken a real liking to me and makes earnest attempts to talk to me. He tells me the name of their Anglican Church is Igreja Santa Maria. He asks if there are any churches named after Saint Mary in the United States, and I tell him that there certainly are – very many! He likes this response as well.

The only thing I feel bad about is that everyone is so cold. Many people actually are wearing winter coats, though I estimate the temperature to be in the low 50s. Of course they only have open windows and no blankets. Overnight I hear the sounds of coughing coming from many huts. For once, though, my own heritage and upbringing is to my advantage; for me the weather is not only comfortable but a positive delight after all the heat and sweat. I only hope my immune system holds out for the rest of the trip.

JUNE 14: Before beginning our morning with the choir, we once again make a detour to the school to present school supplies. I love the optimism of this village. Though tiny and remote, they have taken the time to construct a sign outside their two-room schoolhouse: “EP1 de Magachi” it proudly proclaims: "Escola Primaria Uma de Magachi.” Public School Number 1? I think it will be a while before number 2 comes along…. As I said, I love the optimism, and the school is very well maintained. I am liking Magachi as a village more and more.

Tonight we had dinner in the chief’s “backyard,” their walled-in family compound. We do separate cooking from the family over an open fire in the corner. A granddaughter named Maria who also sings in the choir and whom I estimate to be about twelve years old has apparently been assigned to assist us in whatever way we need. Fortunately our needs are few. We are having spaghetti, but the family is having nsima, which always takes a long time to cook. As we are eating and they are waiting, the chief tells us the story of the name of Magachi. Apparently the Yao were in the village first, and their name for the place was their name for the local river as well: Chizulu. They grew mostly beans, however, so the first Nyanja settlers heard the Yao name for beans all the time: Magachi. That is the name that finally stuck. I think it is actually a nicer sounding name and say so. This seems to charm the chief, who appears to have taken a real liking to me and makes earnest attempts to talk to me. He tells me the name of their Anglican Church is Igreja Santa Maria. He asks if there are any churches named after Saint Mary in the United States, and I tell him that there certainly are – very many! He likes this response as well.

The only thing I feel bad about is that everyone is so cold. Many people actually are wearing winter coats, though I estimate the temperature to be in the low 50s. Of course they only have open windows and no blankets. Overnight I hear the sounds of coughing coming from many huts. For once, though, my own heritage and upbringing is to my advantage; for me the weather is not only comfortable but a positive delight after all the heat and sweat. I only hope my immune system holds out for the rest of the trip.

JUNE 14: Before beginning our morning with the choir, we once again make a detour to the school to present school supplies. I love the optimism of this village. Though tiny and remote, they have taken the time to construct a sign outside their two-room schoolhouse: “EP1 de Magachi” it proudly proclaims: "Escola Primaria Uma de Magachi.” Public School Number 1? I think it will be a while before number 2 comes along…. As I said, I love the optimism, and the school is very well maintained. I am liking Magachi as a village more and more.

The choir of Igreja Anglicana Santa Maria, Magachi. Mr. Barnabas Santhe, choirmaster is on the far right. The serious expressions so many choirs adopt remind me of Nineteenth Century American rural portraiture.

The choir of Igreja Anglicana Santa Maria, Magachi. Mr. Barnabas Santhe, choirmaster is on the far right. The serious expressions so many choirs adopt remind me of Nineteenth Century American rural portraiture. Though scheduled at 9, of course we begin our session at 10. It is indeed mostly adults. They sing two of their songs then want to launch right into learning “Chauta.” I talk them into a breathing and posture lesson first. With the adults separated from the children for the first time in any village, I will be able to give the two different breathing lessons I have always wished I could! I am able to take extra time demonstrating and practicing, then I have the choir try the last song they did using this new posture. The choirmaster, Mr. Barnabas, is astounded at the difference in sound. The second the song is over he jumps over a bench with a huge smile and lunges for my hand for a big handshake and even a high five of sorts – a kind of sideways two person hand clap. Gradually the children were coming in from school. Apparently this school was shorthanded as well, this being salary time, and the teacher felt that sending the children to rehearsal would improve his class size. It made sense to me.

We began to work a bit on dance. They had always been rehearsing in rows, which here invariably means sopranos (almost exclusively children) in the front row, altos (grown women and unchanged boys) in the second, tenors the third and basses in the fourth. One of the problems with this system (among many) is that the children cannot see the adults behind them in order to properly learn the dance. Many choirmasters do not stand in front of their group; rather, they correct them from the side. This is a confusing vantage point for a child, and they frequently do poorly. This choirmaster was so exasperated with one child who was perpetually on the wrong foot that he yelled “Iwe! Ndiwe mzungu?” [“You! What’s the matter with you? Are you white?”] At the first opportunity, I encourage the group to consider rehearsing dance in a circle, so that the less experienced can observe the more experienced and can learn the correct foot to use by observing the two people next to each singer. It takes a few tries, because the children always want to look across and then get confused by the apparent opposite footing, but after a few gentle explanations things get better.

This group, which again is trying to get itself started after years of desultory attempts, has its detractors: a couple of hecklers have come to try to derail the process. One is a young man who apparently has nothing better to do, the other a slightly older woman who was once in the choir and keeps telling them how bad they are and how lazy. Eventually the choir deals with both and tells them they must leave the church. Thankfully, they do.

By the end of the first rehearsal, the choirmaster is beginning to come to the front and center to give crucial directions, the first two rows are together in the dance, and the group has more energy and sound. Unfortunately, the men are not as accurate in their dance as the children are now, but this is a little awkward since the men are the disciplinarians of the group and cannot be directly corrected by a stranger in front of children. I am hoping the circle technique will improve their precision with time.

The afternoon began more or less on time. The group does not have much discipline yet. The ensemble tells the choirmaster when they do not want to sing a song he has suggested and then refuse to sing it. People talk over each other and the choirmaster and sometimes tell him what to do and how to do it. Still, we manage six songs and three videos. We ran “Chauta” with movement, and I manage to hand out the pencils that the University of Rhode Island Music Department has sent as special gifts; they are “magic” pencils that are blue on the outside when cool and white when warm or after being held in the hand. These pencils are a huge hit whenever I can hand them out, but I only have enough if the choirs are under twenty each, and even then I may not have quite enough. This choir passes the test, so they will get their pencils now. Others will just have to wait until the festival, when the twenty singer maximum rule is brought into play. Of course there is no such rule for ensemble size in the villages, thank goodness.

We are not finished until well after five (and don't forget it gets dark here by around six), but it was a very productive day. The choir tells me they will be coming to the festival this year, so that is at least one more choir than before!

Once again on the way back to the compound, I must watch children being cruel to animals. I really do not know how or why dogs and cats stay domesticated here. Most people throw rocks at them and shout “Iwe!” [You!] and “Choka” [the impolite command for “Get out of here!”] frequently accompanied by hitting, though I have not seen any kicking as I have heard happens in nearby cultures. Dogs and cats are never fed anything other than small table scraps if any are left; otherwise they must forage. A cat [mbuyao, I learn from Marcos, not mphaka as in standard Chichewa] came by the compound and gave such a pitiful meow, I wanted to give it something from our dinner, but didn’t dare. I do understand it would be a huge “waste” of food.

At dinner, the chief asks me if I can move to Africa for the rest of my life to teach the villages how to sing songs. I tell him it sounds wonderful, but I don’t know how my wife would feel about it! Joe laughs. The chief asks to see a picture of my family. I have one, but it is on the computer I did not bring on this trip. He tells me to send him one when I get home; he wants to see it.

I look up at the stars, still trying to get used to the changes – the Big Dipper is upside down, spilling its contents towards a North Star that is only imaginary here. The Southern Cross is high in the sky. Orion, who is backwards and always lies down, has already disappeared from view. There is almost always at least one shooting star every night, but tonight all the stars stay in place. As always, some of them seem to change color though: blue to white to red and back. The night is clear and cold, and I am content and getting sleepy. I bid everyone goodnight and go to my tent to settle in.

Tomorrow is a very big hike as we head back home. I feel ready but a little nervous about my first all-day hike. I hope I can do it.

We began to work a bit on dance. They had always been rehearsing in rows, which here invariably means sopranos (almost exclusively children) in the front row, altos (grown women and unchanged boys) in the second, tenors the third and basses in the fourth. One of the problems with this system (among many) is that the children cannot see the adults behind them in order to properly learn the dance. Many choirmasters do not stand in front of their group; rather, they correct them from the side. This is a confusing vantage point for a child, and they frequently do poorly. This choirmaster was so exasperated with one child who was perpetually on the wrong foot that he yelled “Iwe! Ndiwe mzungu?” [“You! What’s the matter with you? Are you white?”] At the first opportunity, I encourage the group to consider rehearsing dance in a circle, so that the less experienced can observe the more experienced and can learn the correct foot to use by observing the two people next to each singer. It takes a few tries, because the children always want to look across and then get confused by the apparent opposite footing, but after a few gentle explanations things get better.

This group, which again is trying to get itself started after years of desultory attempts, has its detractors: a couple of hecklers have come to try to derail the process. One is a young man who apparently has nothing better to do, the other a slightly older woman who was once in the choir and keeps telling them how bad they are and how lazy. Eventually the choir deals with both and tells them they must leave the church. Thankfully, they do.

By the end of the first rehearsal, the choirmaster is beginning to come to the front and center to give crucial directions, the first two rows are together in the dance, and the group has more energy and sound. Unfortunately, the men are not as accurate in their dance as the children are now, but this is a little awkward since the men are the disciplinarians of the group and cannot be directly corrected by a stranger in front of children. I am hoping the circle technique will improve their precision with time.

The afternoon began more or less on time. The group does not have much discipline yet. The ensemble tells the choirmaster when they do not want to sing a song he has suggested and then refuse to sing it. People talk over each other and the choirmaster and sometimes tell him what to do and how to do it. Still, we manage six songs and three videos. We ran “Chauta” with movement, and I manage to hand out the pencils that the University of Rhode Island Music Department has sent as special gifts; they are “magic” pencils that are blue on the outside when cool and white when warm or after being held in the hand. These pencils are a huge hit whenever I can hand them out, but I only have enough if the choirs are under twenty each, and even then I may not have quite enough. This choir passes the test, so they will get their pencils now. Others will just have to wait until the festival, when the twenty singer maximum rule is brought into play. Of course there is no such rule for ensemble size in the villages, thank goodness.

We are not finished until well after five (and don't forget it gets dark here by around six), but it was a very productive day. The choir tells me they will be coming to the festival this year, so that is at least one more choir than before!

Once again on the way back to the compound, I must watch children being cruel to animals. I really do not know how or why dogs and cats stay domesticated here. Most people throw rocks at them and shout “Iwe!” [You!] and “Choka” [the impolite command for “Get out of here!”] frequently accompanied by hitting, though I have not seen any kicking as I have heard happens in nearby cultures. Dogs and cats are never fed anything other than small table scraps if any are left; otherwise they must forage. A cat [mbuyao, I learn from Marcos, not mphaka as in standard Chichewa] came by the compound and gave such a pitiful meow, I wanted to give it something from our dinner, but didn’t dare. I do understand it would be a huge “waste” of food.

At dinner, the chief asks me if I can move to Africa for the rest of my life to teach the villages how to sing songs. I tell him it sounds wonderful, but I don’t know how my wife would feel about it! Joe laughs. The chief asks to see a picture of my family. I have one, but it is on the computer I did not bring on this trip. He tells me to send him one when I get home; he wants to see it.

I look up at the stars, still trying to get used to the changes – the Big Dipper is upside down, spilling its contents towards a North Star that is only imaginary here. The Southern Cross is high in the sky. Orion, who is backwards and always lies down, has already disappeared from view. There is almost always at least one shooting star every night, but tonight all the stars stay in place. As always, some of them seem to change color though: blue to white to red and back. The night is clear and cold, and I am content and getting sleepy. I bid everyone goodnight and go to my tent to settle in.

Tomorrow is a very big hike as we head back home. I feel ready but a little nervous about my first all-day hike. I hope I can do it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed